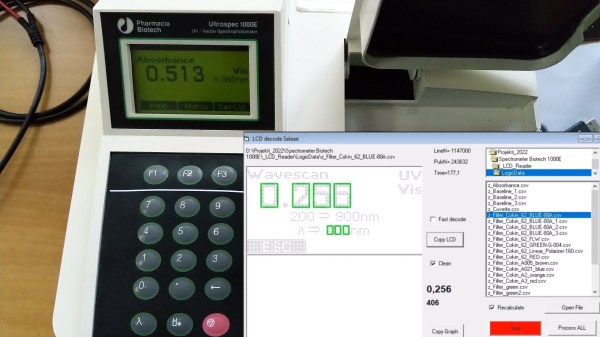

[Jure Spiler] was at a flea market and got himself a spectrophotometer — a device that measures absorbance and transmittance of light at different wavelengths. This particular model seems to be about 25 years old, and it’s controlled by a built-in keyboard and uses a graphical LCD to display collected data. That might have been acceptable when it was made, but it wasn’t enough for [Jure]. Since he wanted to plot the spectrophotometry data and be able to save it into a CSV file, hacking ensued.

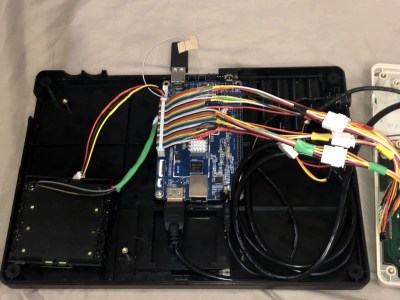

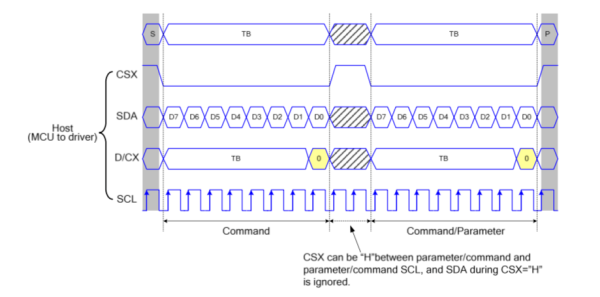

He decided to tap into the the display communication lines. This 128×64 graphical display, PC-1206B, uses a 8-bit interface, so with a 16-channel logic analyzer, he could see the data being sent to the display. He even wrote decoder software – taking CSV files from the logic analyzer and using primitive optical recognition on the decoded pixels to determine the digits being shown, and drawing a nice wavelength to absorbance graph. From there, he set out to make a standalone device sniffing the data bus and creating a stream of data he could send to a computer for storage and processing.

[Jure] stumbled into a roadblock, however, when he tried to use an Arduino for this task. Even using a sped-up GPIO library (as opposed to notoriously inefficient

[Jure] stumbled into a roadblock, however, when he tried to use an Arduino for this task. Even using a sped-up GPIO library (as opposed to notoriously inefficient digitalRead), he couldn’t get a readout frequency higher than 80 KHz – with the required IO readout rate deemed as 1 MHz, something else would be called for. We do wonder if something like RP2040 with its PIO machinery would be better for making such captures.

At that point, however, he found out that there’s undocumented serial output on one of the pins of the spectrophotometer’s expansion port, and is currently investigating that, having shelved the LCD sniffing direction. Nevertheless, this serves as yet another example for us, for those times when an LCD connection is all that we can make use of.

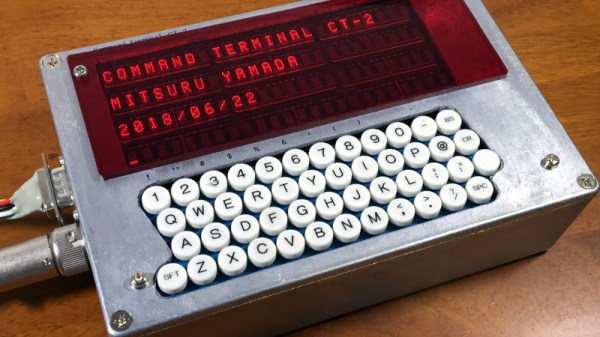

We’ve seen hackers sniff LCD interfaces to get data from reflow ovens, take screenshots from Game Boys and even equip them with HDMI and VGA ports afterwards. With a skill like this, you can even give a new life to a vintage calculator with a decayed display! Got an LCD-equipped device but unsure about which specific controller it uses? We’ve talked about that!

Continue reading “Exporting Data From Old Gear Through LCD Sniffing”