You’ve got to hand it to [Tom Stanton] – he really thinks outside the box. And potentially outside the atmosphere, to wit: we present his reaction control gas thruster-controlled drone.

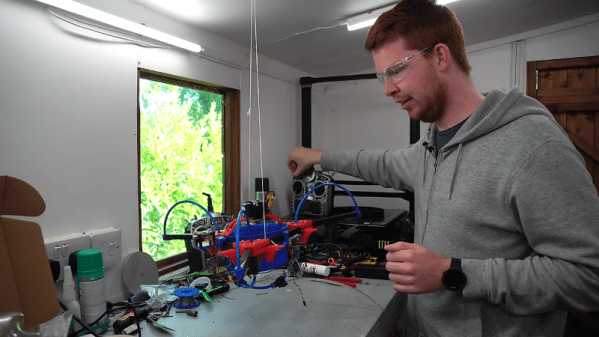

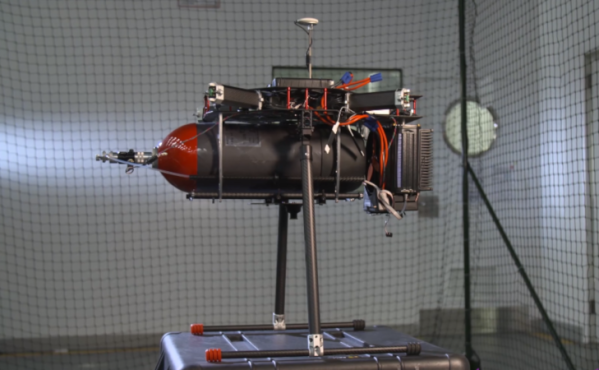

Before anyone gets too excited, [Tom] isn’t building drones for use in a vacuum, although we can certainly see a use case for such devices. This is more of a hybrid affair, with counter-rotating props mounted in a centrally located duct providing the lift and the yaw control. Flanking that is a triangular frame supporting three two-liter soda bottle air reservoirs, each of which supplies a down-firing nozzle at each apex of the triangle. Solenoid valves control the flow of compressed air from the bottles to the nozzles, providing thrust to stabilize the roll and pitch axes. As there aren’t many off-the-shelf flight control systems set up for reaction control, [Tom] had to improvise thruster control; an Arduino watches the throttle signals normally sent to a drone’s motors and fires the solenoids when they get to a preset threshold. It took some tuning, but [Tom] was eventually able to get a stable, untethered hover. And he’s right – the RCS jets do sound amazing when they’re firing, as long as the main motors are off.

This looks as though it has a lot of potential, and we’d love to see it developed more. It reminds us a bit of this ducted-prop drone, another great example of stretching conventional drone control concepts to the limit.

Continue reading “Unconventional Drone Uses Gas Thrusters For Control”