It is a classic problem. You want data for use in your program but it is on a webpage. Some websites have an API, of course, but usually, you are on your own. You can load the whole page via HTTP and parse it. Or you can use some tools to “scrape” the site. One interesting way to do this is woob — web outside of browsers.

The system uses a series of backends tailored at particular sites. There’s a collection of official backends, and you can also create your own. Once you have a backend, you can configure it and use it from Python. Here’s an example of finding a bank account balance:

>>> from woob.core import Woob

>>> from woob.capabilities.bank import CapBank

>>> w = Woob()

>>> w.load_backends(CapBank)

{'societegenerale': <Backend 'societegenerale'>, 'creditmutuel': <Backend 'creditmutuel'>}

>>> pprint(list(w.iter_accounts()))

[<Account id='7418529638527412' label=u'Compte de ch\xe8ques'>,

<Account id='9876543216549871' label=u'Livret A'>,

<Account id='123456789123456789123EUR' label=u'C/C Eurocompte Confort M Roger Philibert'>]

>>> acc = next(iter(w.iter_accounts()))

>>> acc.balance

Decimal('87.32')

The list of available backends is impressive, but eventually, you’ll want to create your own modules. Thankfully, there’s plenty of documentation about how to do that. The framework allows you to post data to the website and easily read the results. Each backend also has a test which can detect if a change in the website breaks the code, which is a common problem with such schemes.

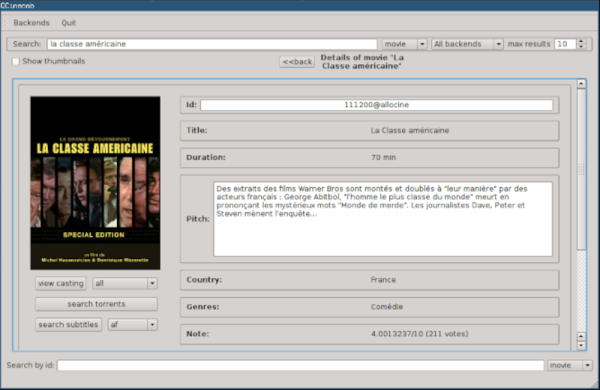

We didn’t see a Hackaday backend. Too bad. There are, however, many application examples, both console-based and using QT. For example, you can search for movies, manage recipes, or dating sites.

Of course, there are many approaches possible to this problem. Maybe you need to find out when the next train is leaving.