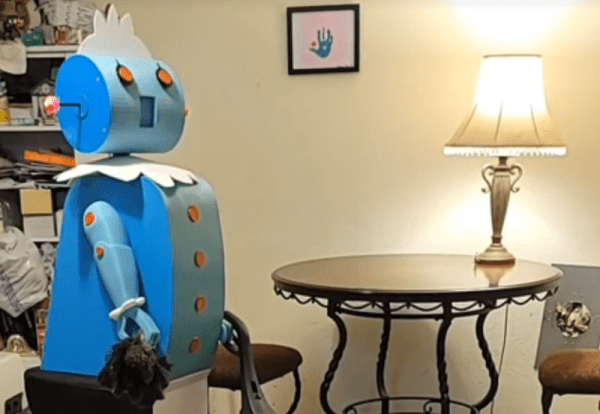

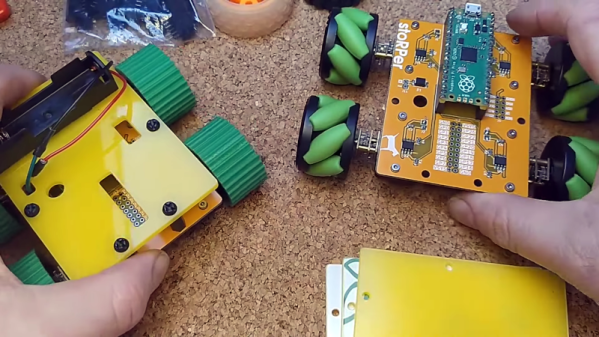

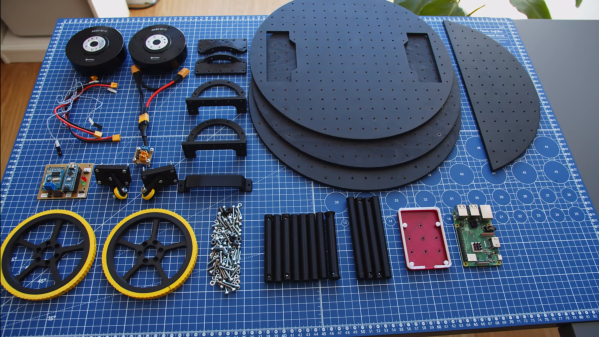

A LiIon pack might just be exactly what you need for powering a device of yours. Whether it’s a laptop, or a robot, or a custom e-scooter, a CPAP machine, there’s likely a LiIon cell configuration that would work perfectly for your needs. Last time, we talked quite a bit about the parameters you should know about when working with existing LiIon packs or building a new one – configurations, voltage notations, capacity and internal resistance, and things to watch out for if you’re just itching to put some cells together.

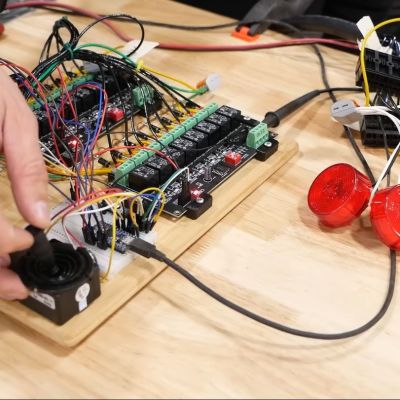

Now, you might be at the edge your seat, wondering what kind of configuration do you need? What target voltage would be best for your task? What’s the physical arrangement of the pack that you can afford? What are the safety considerations? And, given those, what kind of electronics do you need?

Picking The Pack Configuration

Pack configurations are well described by XsYp:X serial stages, each stage having Y cells in parallel. It’s important that every stage is the same as all the others in as many parameters as possible – unbalanced stages will bring you trouble.

To get the pack’s nominal voltage, you multiply X (number of stages) by 3.7 V, because this is where your pack will spend most of its time. For example, a 3s pack will have 11.1 V nominal voltage. Check your cell’s datasheet – it tends to have all sorts of nice graphs, so you can calculate the nominal voltage more exactly for the kind of current you’d expect to draw. For instance, the specific cells I use in a device of mine, will spend most of their time at 3.5 V, so I need to adjust my voltage expectations to 10.5 V accordingly if I’m to stack a few of them together.

To get the pack’s nominal voltage, you multiply X (number of stages) by 3.7 V, because this is where your pack will spend most of its time. For example, a 3s pack will have 11.1 V nominal voltage. Check your cell’s datasheet – it tends to have all sorts of nice graphs, so you can calculate the nominal voltage more exactly for the kind of current you’d expect to draw. For instance, the specific cells I use in a device of mine, will spend most of their time at 3.5 V, so I need to adjust my voltage expectations to 10.5 V accordingly if I’m to stack a few of them together.

Now, where do you want to fit your pack? This will determine the voltage. If you want to quickly power a device that expects 12 V, the 10.5 V to 11.1 V of a 3s config should work wonders. If your device detects undervoltage at 10.5V, however, you might want to consider adding one more stage.

How much current do you want to draw? For the cells you are using, open their spec sheet yet again, take the max current draw per cell, derate it by like 50%, and see how many cells you need to add to match your current draw. Then, add parallel cells as needed to get the capacity you desire and fit the physical footprint you’re aiming for. Continue reading “Ultimate Power: Lithium-Ion Packs Need Some Extra Circuitry”