Retrocomputing is as much about physical preservation as it is about electronics and computer science. Plastic is an awful material when it comes to decade-long timescales, and the forces of sun, air and water are unrelenting on these materials. [Drygol] has long experimented with techniques to preserve and refresh keycaps, and decided to try some fun vacuum forming techniques for something new. It sadly didn’t go to plan, however.

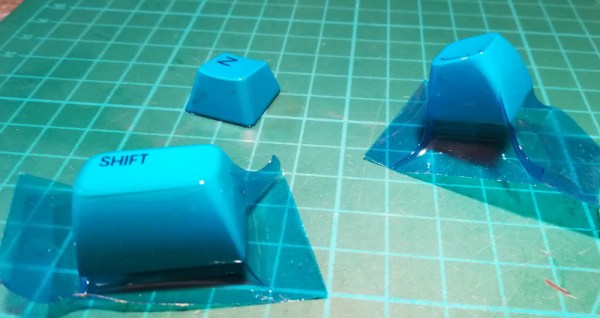

The basic idea was to use a vacuum-forming machine to coat keycaps in a thin layer of translucent plastic, for both aesthetic benefit and to preserve them from falling apart. Initial small-scale tests were promising, creating a key with a tight, form-fitting blue plastic wrap through which the original labels were still visible.

However, scaling up the process proved fraught. Uneven heating of the plastic film and a lack of rigidity in the carriage used to stretch it over the keycaps led to poor results. The final product showed many wrinkles and was distinctly unappealing.

[Drygol] isn’t giving up however, and plans to build a new vacuum table with greater performance. We can imagine this technique being an accessible way to colorize keycaps for a vintage cyberdeck or chiptune rig, without permanently modifying the keys. If you’ve got the inside knowledge on how to make this work, sound off in the comments.

We’ve seen [Drygol]’s work in this space before, too, like this extreme modded Amiga. If you’re executing your own retro repairs, be sure to drop us a line!