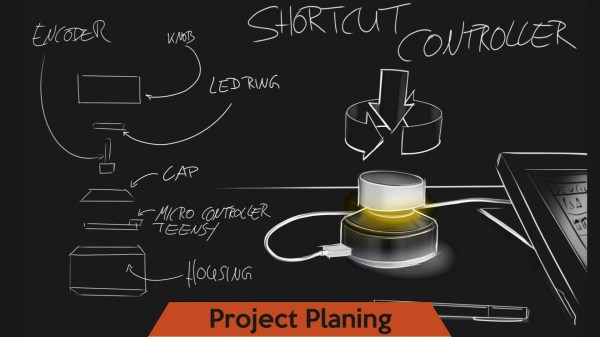

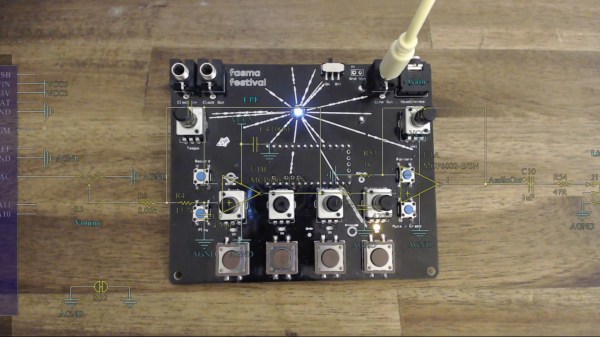

People always tell us that their favorite part about using a computer is mashing out the exact same key sequences over and over, day in, day out. Then, there are people like [Benni] who would rather make a microcontroller do the repetitive work at the touch of a stylish USB peripheral. Those people who enjoy the extra typing also seem to love adding new proprietary software to their computer all the time, but they are out of luck again because this dial acts as a keyboard and mouse so they can’t even install that bloated software when they work at a friend’s computer. Sorry folks, some of you are out of luck.

Rotary encoders as computer inputs are not new and commercial versions have been around for years, but they are niche enough to be awfully expensive to an end-user. The short BOM and immense versatility will make some people reconsider adding one to their own workstations. In the video below, screen images are rotated to get the right angle before drawing a line just like someone would do with a piece of paper. Another demonstration reminds of us XKCD by cycling through the undo and redo functions which gives you a reversible timeline of your work.

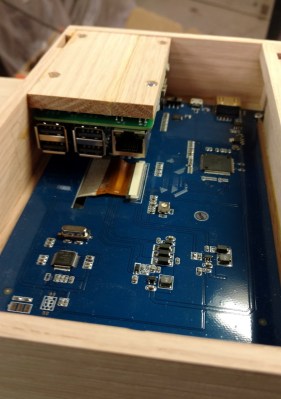

If you like your off-hand macro enabler to have more twists and buttons, we have you covered, or maybe you only want them some of the time.