You should be used to our posting the hacks that didn’t quite go according to plan under our Fail Of The Week heading, things that should have worked, but due to unexpected factors, didn’t. They are the fault, if that’s not too strong a term, of the person making whatever the project is, and we feature them not in a spirit of mockery but one of commiseration and enlightenment.

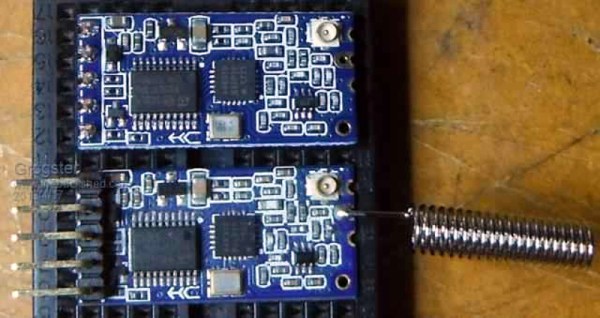

This FOTW is a little different, because it reveals itself to have nothing to do with its originator. [Grogster] was using the widely-available HC-12 serial wireless modules, or clones or even possibly fakes thereof, and found that the modules would not talk to each other. Closer inspection found that the modules with the lack of intercommunication came from different batches, and possibly different manufacturers. Their circuits and components appeared identical, so what could possibly be up?

The problem was traced to the two batches of modules having different frequencies, one being 37 kHz ahead of the other. This was in turn traced to the crystal on board the off-frequency module, the 30 MHz component providing the frequency reference for the Si4463 radio chip was significantly out of spec. The manufacturer had used a cheap source of the component, resulting in modules which would talk to each other but not to the rest of the world’s HC-12s.

If there is a lesson to be extracted from this, it is to be reminded that even when cheap components or modules look as they should, and indeed even when they appear to work as they should, there can still be unexpected ways in which they can let you down. It has given us an interesting opportunity to learn about the HC-12, with its onboard STM8 CPU and one of the always-fascinating Silicon Labs radio chips. If you want to know more about the HC-12 module, we linked to a more in-depth look at it a couple of years ago.

Thanks [Manuka] for the tip.