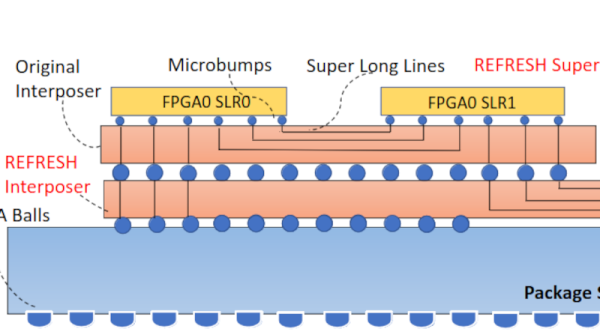

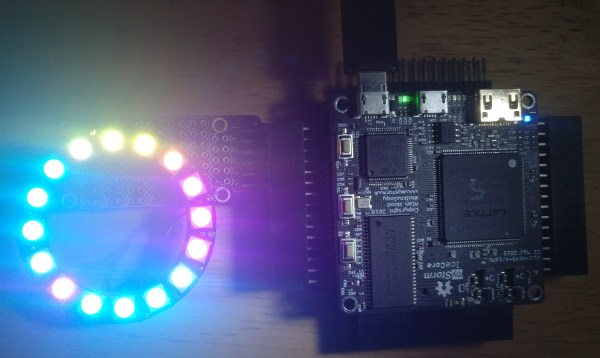

If you really want to look at how much something costs, you need to look at total cost of ownership, not just the sticker price. Same goes for things like pollution and carbon footprint. A vehicle, for example, might have a low carbon footprint in operation but require more carbon in the manufacturing or disposal processes. Researchers have noted that FPGA accelerators get replaced and may wind up as e-waste in as little as two years. They propose REFRESH, an architecture that recycles old FPGAs into new ones by joining multiple FPGA dice with a simple interposer to coordinate the work.

The idea is not as radical as it might first seem. Many modern chips use chiplets anyway, so this is a reasonable extension of that idea. You simply need a way to harvest the old devices.