Here’s an exercise for you: type “crystals” into your favorite search engine and see what you get. If you’re anything like us, you’ll get a bunch of pseudoscientific posts about the healing power of crystals, along with offers to buy the same at exorbitant prices. But woo-woo aside, certain crystals do have seemingly magical powers — like the ability to turn light from one color into another.

None of this is magic, of course. Rather, as optics aficionado [Les Wright] explains, non-linear optics is all about physics. Big physics, too, like the kind that made the National Ignition Facility the first fusion research outfit to reach the “break-even” point, at least in terms of optical energy. To do so, they need to convert megajoules of infrared laser beams all the way across the visible spectrum into the ultraviolet, relying on huge crystals of deuterated potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP) to do so. Depending on how they’re cut, crystals of these sorts have non-linear optical properties like second-harmonic generation, which combines two input photons into a single output photon with twice the energy of the original. This results in a halving of the wavelength of the input, which doubles the frequency.

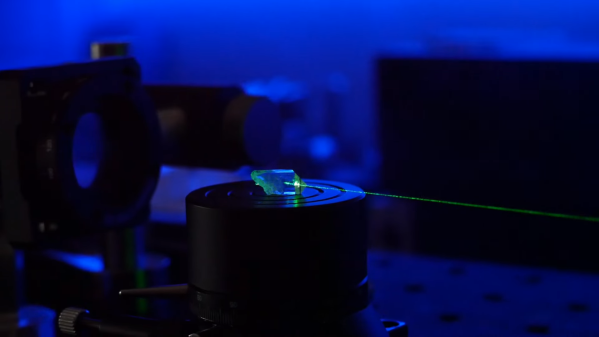

While the process used at the NIF produces crystals of enormous proportions, [Les] has more modest needs and thus a simpler process. His KDP is an off-the-shelf chemical, nothing fancy about it, which is added to boiling water to make a saturated solution. A little of the solution is poured out into a watch glass to make seed crystals, and everything is allowed to cool slowly. A nice seed crystal is glued to a piece of monofilament fishing line and suspended in the saturated solution, and with enough time a good-sized crystal forms. Placed into the beam path of a 1,064 nm IR laser and rotated carefully relative to the beam, the crystal easily produces a brilliant green laser output.

This is fascinating stuff, and we’re looking forward to seeing where [Les] goes with this. Polishing the crystals to make them optically cleaner would be a good next step, as would perhaps growing even larger crystals.

Continue reading “Growing Simple Crystals For Non-Linear Optics Experiments”