The Raspberry Pi and Teensy 3 both have I2S interfaces, and that means these boards can be used to play very high quality audio. A codec and an I2S interface is one thing, but turning that digital stream into a quality analog output is another thing entirely. You need only look at audiophile forums for enough mis- and disinformation for that evidence.

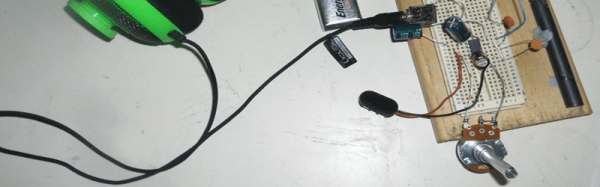

For his Hackaday Prize entry [William Hollender] is building an audio board for the Teensy 3.x. It features very high-end opamps, the right filters, and the correct topology to turn a digital audio stream into an analog signal that would please the most temperamental ear.

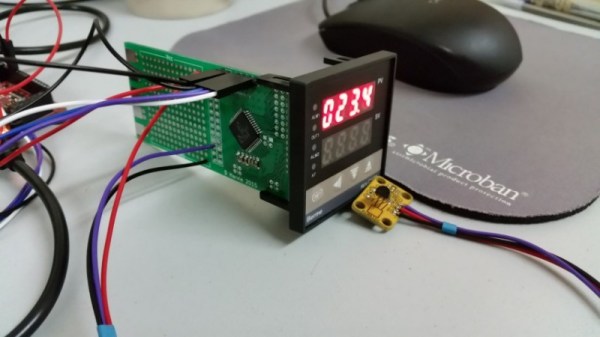

The Teensy Super Audio Board uses the Cirrus CS4272 audio codec chip, a high quality chip that can handle sample rates of up to 192kHz at 24 bit depth. This chip doesn’t include the analog input and output buffers, and this means [William] has quite a build in front of him. This means using high quality opamps, low noise power supplies, and knowing how to build a circuit and measure its noise.

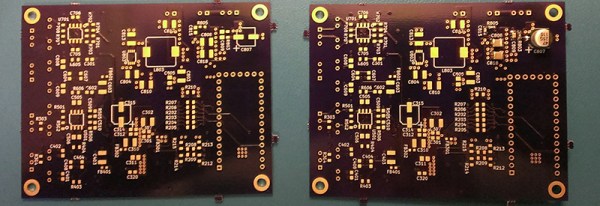

So far, the tests revealed incredible dynamic range, flatness, and frequency response of this tiny little board. It also works with the Raspberry Pi. Now it’s just a matter of getting a few more of these boards put together for the Best Product part of the Hackaday Prize.

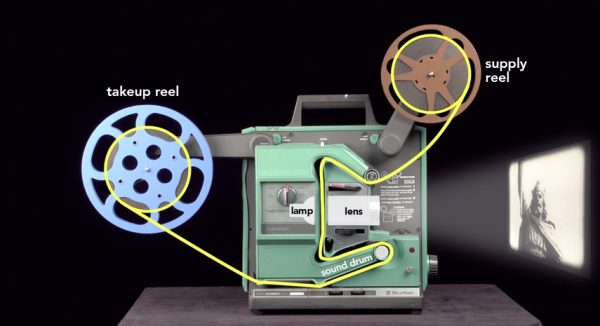

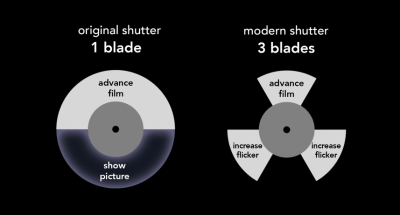

Film is projected at a rate of 24 frames per second, which is sufficient to create the POV illusion. A projector’s shutter inserts itself between the lamp and the lens, blocking the light to prevent projection of the film’s physical movement. But these short periods of darkness, or flicker, present a problem. Originally, shutters were made in the shape of a semi-circle, so they block the light half of the time. Someone figured out that increasing the flicker rate to 60-70 times per second would have the effect of constant brightness. And so the modern shutter has three blades: one blocks projection of the film’s movement, and the other two simply increase flicker.

Film is projected at a rate of 24 frames per second, which is sufficient to create the POV illusion. A projector’s shutter inserts itself between the lamp and the lens, blocking the light to prevent projection of the film’s physical movement. But these short periods of darkness, or flicker, present a problem. Originally, shutters were made in the shape of a semi-circle, so they block the light half of the time. Someone figured out that increasing the flicker rate to 60-70 times per second would have the effect of constant brightness. And so the modern shutter has three blades: one blocks projection of the film’s movement, and the other two simply increase flicker.