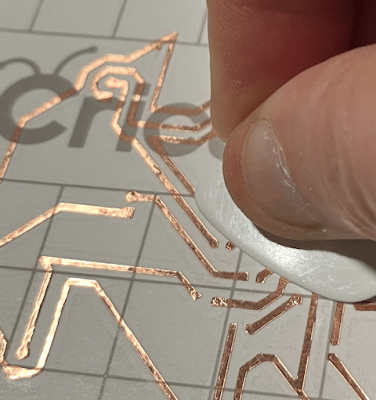

We just love a good DIY tool project, and more so when it’s something that we can actually use cobbled together from stuff in our closet, or hacked out of cheap “toys”. This week we saw both a superb Pi Pico-based logic analyzer and yet another software frontend for the RTL-SDR dongle, and they both had us thinking of how good we have it.

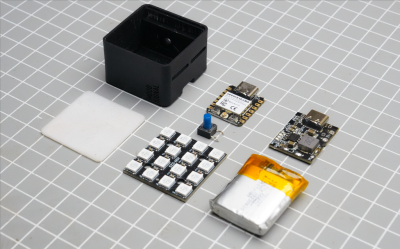

If you don’t already have a logic analyzer, or if you have one of those super-cheap 8-channel jobbies, it might be worth your while to check out the Pico firmware simply because it gets you 24 channels, which is more than you’ll ever need™. At the low price of $4, maybe a little more if you need to add level shifters to the circuit to allow for 5 V inputs, you could do a lot worse for less than the price of a fancy sweet coffee beverage.

And the RTL dongle; don’t get us started on this marvel of radio hacking. If you vaguely have interest in RF, it’s the most amazing bargain, and ever-improving software just keeps adding functionality. The post above adds HTML5 support for the RTL-SDR, allowing you to drive it with code you host on a web page, which makes the entire experience not only cheap, but painless. Talk about a gateway drug! If you don’t have an RTL-SDR, just go out and buy one. Trust me.

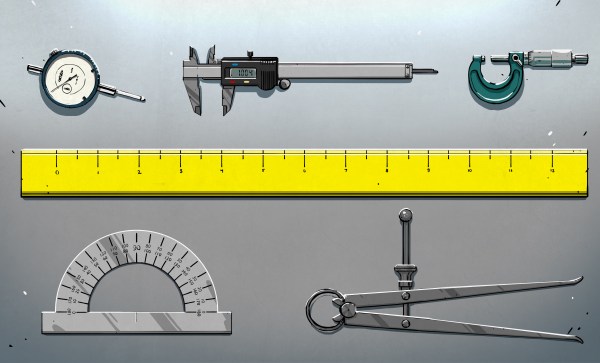

What both of these hacker tools have in common, of course, is good support by a bunch of free and open software that makes them do what they do. This software enables a very simple piece of hardware to carry out what used to be high-end lab equipment functions, for almost nothing. This has an amazing democratizing effect, and paves the way for the next generation of projects and hackers. I can’t think of a better way to spend $20.