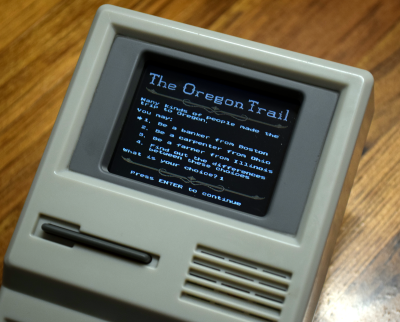

What do you do when you’re working with some vintage ICs and one of the tiny legs pops off? That’s what happened to [Kotomi] when working with an old Super Nintendo. A single lead for the sound chip just snapped off, leaving [Kotomi] one pin short of a working system (the Google Translatrix). This is something that can be fixed, provided you have a steady hand and a rotary tool that’s spinning at thousands of RPM.

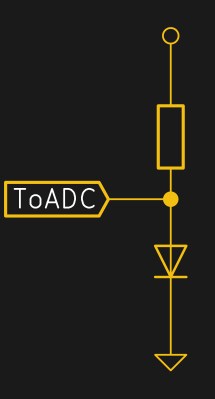

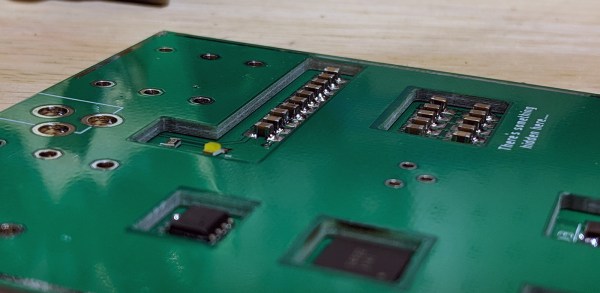

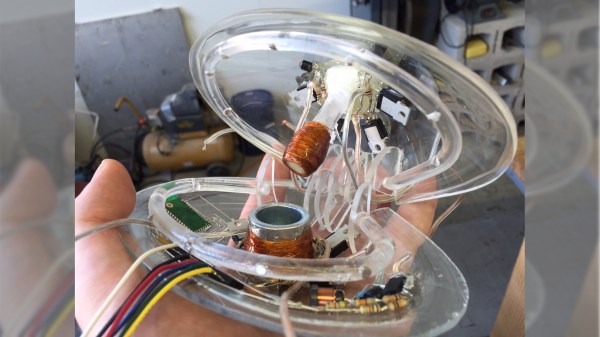

Fixing this problem relies on a little bit of knowledge of how integrated circuits are built. There’s a small square of silicon in there, but this tiny die is bonded to a metal leadframe, which looks like the ribcage of a robotic centipede. This leadframe is covered in epoxy, the pins are bent down, and you have an IC. Removing just a tiny bit of epoxy grants access to the leadframe which you can then solder to. Don’t breathe the repair, it’s not pretty, but it does work.

While this technique makes use of a Dremel to break into the chewy nougat center of a vintage chip, and in some ways this could be called decapsulation, it really isn’t. We’ve seen people drop acid to get to the center of a chip and a really hot torch will get to the middle of a ceramic chip, but this technique is just accessing the lead frame of the IC. All ICs have a stamped (or photoetched) metal frame to which the silicone die is bonded. Running a Dremel against some epoxy doesn’t access the silicon, but it does grant access to the signals coming off the chip.

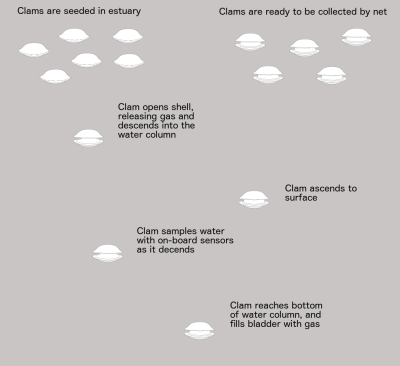

The clams contain the electronics, sensors, and means of descending and ascending within their shells. A bunch of them are dropped overboard on the surface. Their shells open, allowing the gas within to escape and they sink. As they descend they sample the water. When they reach the bottom, gas fills a bladder and they ascend back to the surface with their data where they’re collected in a net.

The clams contain the electronics, sensors, and means of descending and ascending within their shells. A bunch of them are dropped overboard on the surface. Their shells open, allowing the gas within to escape and they sink. As they descend they sample the water. When they reach the bottom, gas fills a bladder and they ascend back to the surface with their data where they’re collected in a net.