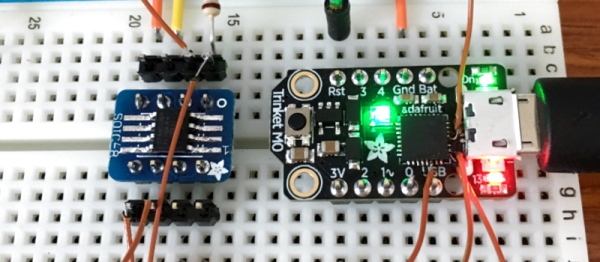

We’re suckers for miniaturization projects. Stuff anything into a small enough package and you’ve probably got our attention. Make that something both tiny and useful, like this 5-volt to 3.3-volt converter in a TO-220 sized package, and that’s something to get excited about. It’s a switch mode power supply that takes the same space as a traditional linear regulator.

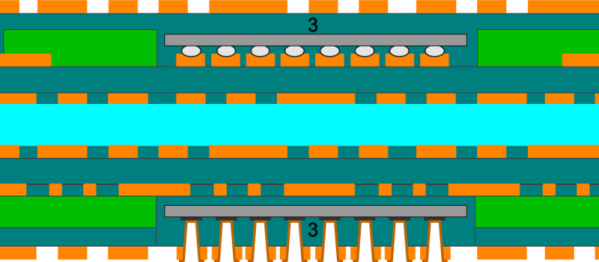

Granted, the heavy lifting in [Kevin Hubbard]’s diminutive buck converter is done by a PAM2305 DC-DC step-down converter chip which needs only a few supporting components. But the engineering [Kevin] put into this to squeeze everything onto a scrap of PCB 9-mm on a side is impressive. The largest passive on the board is the inductor in 0805. Everything else is in 0603, so you’ll be putting your SMD soldering skills to the test if you decide to make this. Check the video after the break for a speedrun through the hand soldering process.

The total BOM including the open-source PCB only runs a buck or two, and the end result is a supply with steady 750-mA output that can handle a 1-A surge for five seconds. We wonder if a small heatsink tab might not help that; along with some black epoxy potting, it would at least complete the TO-220 look.

[Kevin]’s Black Mesa Labs has a history of turning out interesting projects, from a legit video card for Arduino to a 100-watt hotplate for reflow work that’s the size of a silver dollar. We’re looking forward to whatever’s next — assuming we can see it.

Continue reading “A DIY 5V-3V Switching Converter In The Space Of A TO-220 Package”