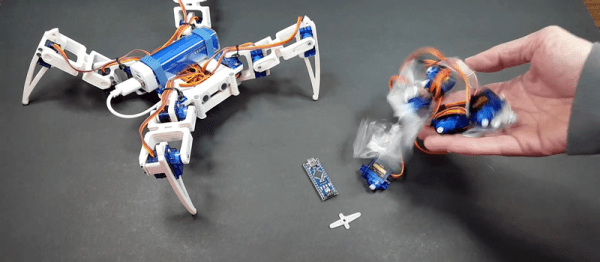

Although we have strong suspicions that the model’s designer failed entomology, this spider robot is very cool. [Hari Wiguna] made one, and is justifiably thrilled with the results. (Watch his summary on YouTube embedded below.)

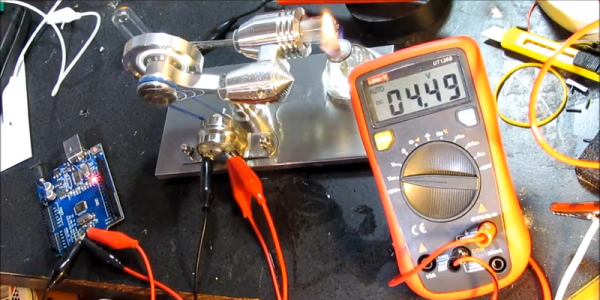

Thanks to [Regis Hsu]’s nice design, all [Hari] had to do was order a hexapod’s dozen 9g servos for around $20, print out the parts, attach an Arduino clone, and he was done. We really like the cutouts in the printed parts that nicely fit the servo horns. [Hari] says the calibration procedure is a snap; you run a sketch that sets all the servos to a known position and then tighten the legs in place. Very slick.

The parts should print without support on basically any printer. [Hari]’s is kinda janky and exhibits all sorts of layer-to-layer irregularities (sorry, man!) but the robot works perfectly. Which is not to say that [Hari] doesn’t have assembly skills — check out the world’s smallest (?) RGB LED cube if you think this guy can’t solder. Of course, you can entirely sidestep the 3D-printed parts and just fix a bunch of servos together and call it a robot. It’s harder to make building a four-legger any easier than these two projects. What are you waiting for?

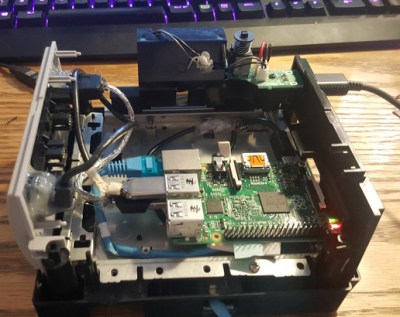

Time marches on, and after a while, the Raspberry Pi 2 was released. By this time, retro emulation was hitting the big time, and [Liam] decided it was time for an upgrade. He disassembled this Nintendo console again, routed new wires and inputs to the original controller ports, and used a Dremel to route a few holes for the HDMI and SD card slot.

Time marches on, and after a while, the Raspberry Pi 2 was released. By this time, retro emulation was hitting the big time, and [Liam] decided it was time for an upgrade. He disassembled this Nintendo console again, routed new wires and inputs to the original controller ports, and used a Dremel to route a few holes for the HDMI and SD card slot.