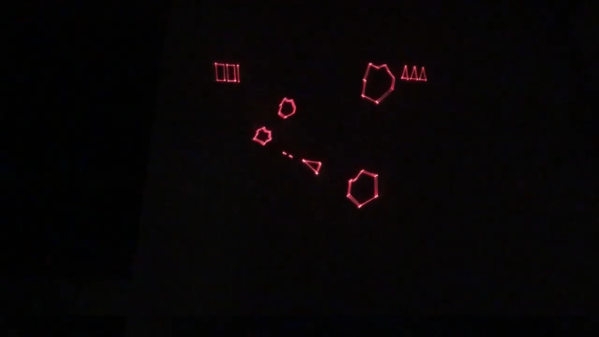

Most people find two problems when it comes to flip-dot displays: where to buy them and how to drive them. If you’re [Pierre Muth] you level up and add the challenge of driving them fast enough to rival non-mechanical displays like LCDs. It was a success, resulting in a novel and fast way of controlling flip-dot displays.

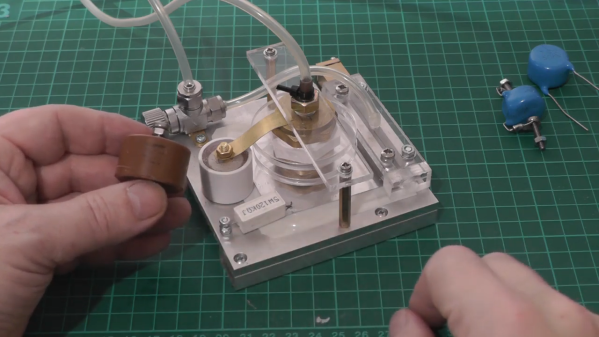

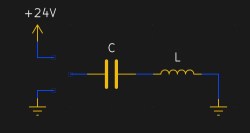

The problem comes in needing to reverse the polarity of the coil to achieve both set and unset states. Here [Pierre] has a very interesting idea: instead of working out a way to change the connections of the coils between source and sink, he’s using a capacitor on one side that can be driven high or low to flip the dot.

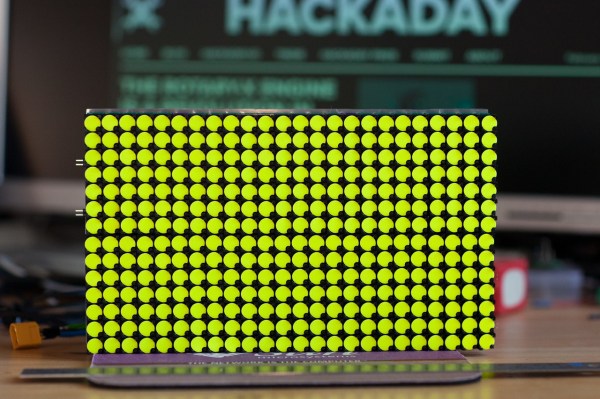

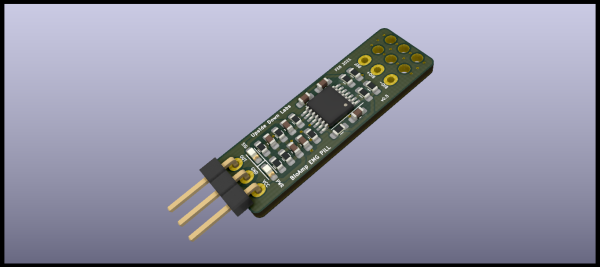

Using this technique, charging the capacitor will give enough kick to flip the dot on the display. The same will happen when discharged (flipping the dot back), with the added benefit of not using additional power since the capacitor is already charged from setting the pixel. A circuit board was designed with CMOS to control each capacitor. A PCB is mounted to the back of a 7-pixel strip, creating modules that are formed into a larger display using SPI to cascade data from one to the next. The result, as you can see after the break, does a fantastic job of playing Bad Apple on the 24×14 matrix. If you have visions of one of these on your own desk, the design files and source code are available. Buying the pixels for a display this size is surprisingly affordable at about 100 €.

Using this technique, charging the capacitor will give enough kick to flip the dot on the display. The same will happen when discharged (flipping the dot back), with the added benefit of not using additional power since the capacitor is already charged from setting the pixel. A circuit board was designed with CMOS to control each capacitor. A PCB is mounted to the back of a 7-pixel strip, creating modules that are formed into a larger display using SPI to cascade data from one to the next. The result, as you can see after the break, does a fantastic job of playing Bad Apple on the 24×14 matrix. If you have visions of one of these on your own desk, the design files and source code are available. Buying the pixels for a display this size is surprisingly affordable at about 100 €.

We’re a bit jealous of all the fun displays [Pierre] has been working on. He previously built a 384 neon bulb display that he was showing off last Autumn.

Continue reading “30 FPS Flip-Dot Display Uses Cool Capacitor Trick”