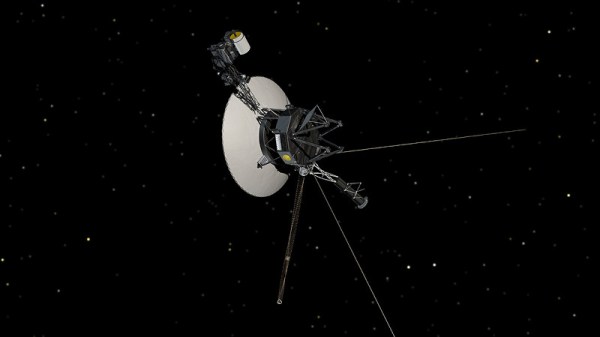

For months, there has been a rising fear that we may have to say farewell to the Voyager 1 spacecraft after it began to send back garbled data. Now, in a sudden twist, Voyager 1 sent back a read-out of the Flight Data Subsystem (FDS) memory after a “poke” command, which both gives some hope that the spacecraft is in a better condition than feared while also allows engineers to dig through the returned memory read-out for clues. Although this data was not sent in the format that the FDS is supposed to use when it’s working correctly, it’s nevertheless readable.

It was previously suspected that the issue lay with the telemetry modulation unit (TMU), but has since been nailed down to the FDS itself. This comes after NASA engineers have been updating the firmware on both spacecraft to extend their lifespan, but it’s too early to consider this as a possible reason. Now, as a result of the “poke” instruction – which commands the computer to try different sequences in its firmware in case part of it has been corrupted – engineers can compare it to previous downloads to hopefully figure out the cause behind the FDS problems and a possible solution.

Inspired by this news of the decoded memory download, Nadia Drake – daughter of Frank Drake – wrote about how it affects not only the engineers who have worked on the Voyager mission for the past decades but also her own thoughts about the two Voyager spacecraft. Not only do they form a lasting reminder of her father and so many of his colleagues, but the silence that would follow if we can no longer communicate with these spacecraft would be profound. Still, this new hope is better than the earlier news about this plucky little spaceship.

Thanks to [Mark Stevens] for the tip.