The dramatic price reductions we’ve seen on resin 3D printers over the last couple of years have been very exciting, as it means more people are finally getting access to this impressive technology. But what newcomers might not realize is that the cost of the printer itself is only part of your initial investment. Resin printed parts need to be washed and cured before they’re ready to be put into service, and unless you want to do it all by hand, that means buying a second machine to do the post-printing treatment.

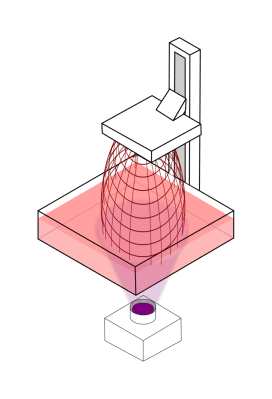

Not sure he wanted to spend the money on a dedicated machine just yet, [Chris Chimienti] decided to take an unusual approach and modify one of his filament-based 3D printers to handle wash and cure duty. His clever enclosure slips over the considerable Z-axis of a Anet ET5X printer, and includes banks of UV LEDs and fans to circulate the air and speed up the drying process.

The curing part is easy enough to understand, but how does it do the washing? You simply put a container of 70% isopropyl alcohol (IPA) on the printer’s bed, and place the part to be washed into a basket that hangs from the printer’s extruder. Custom Python software is used to generate G-code that commands the printer to dip the part in the alcohol and swish it back and forth to give it a good rinse.

Once the specified time has elapsed, the printer raises the part up into the enclosure and kicks on the LEDs to begin the next phase of the process. The whole system is automated through an OctoPrint plugin, and while the relatively low speed of the printer’s movement means the “washing” cycle might not be quite as energetic as we’d like, it’s definitely a very slick solution.

[Chris] provides an extensive overview of the project in the latest video on his YouTube channel, Embrace Racing. In it he explains that the concept could certainly be adapted for use on printers other than the Anet ET5X, but that it’s considerable build volume makes it an ideal candidate for conversion. Of course it’s also possible to use the foam board enclosure by itself as a curing chamber, though you’ll still need to wash the part in IPA ahead of time.

This is perhaps one of the most unusual wash and cure systems we’ve seen here at Hackaday, but we appreciate the fact that [Chris] based the whole thing on the idea that you’ve probably got a FDM printer sitting nearby that otherwise goes unused when you’re working with resin. If that’s not the case for you, putting together a more traditional UV curing chamber is an easy enough project.

Continue reading “Add-On Lets FDM 3D Printer Wash And Cure Resin Parts”