Ever find yourself with nineteen nameless robot vacuums lying around? No? Well, [Aaron Christophel] likes to live a different life, filled with zebra print robots (translated). After tearing a couple down, only ten vacuums remain — casualties are to be expected. Through their sacrifice, he found a STM32F101VBT6 processor acting as the brains for the survivors. Coincidentally, there’s a project called STM32duino designed to get those processors working with the Arduino IDE we either love or hate. [Aaron Christophel] quickly added a variant board through the project and buckled down.

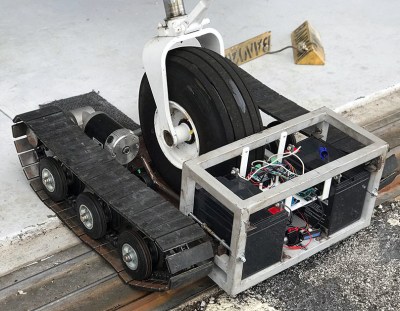

Of course, he simply had to get BLINK up and running, using the back-light of the LCD screen on top of the robots. From there, the STM32 processors gave him a whole 80 GPIO pins to play with. With a considerable amount of tinkering, he had every sensor, motor, and light under his control. Considering how each of them came with a remote control, several infra-red sensors, and wheels, [Aaron Christophel] now has a small robotic fleet at his beck and call. His workshop must be immaculate by now. Maybe he’ll add a way for the vacuums to communicate with each other next. One robot gets the job done, but a whole team gets the job done in style, especially with a zebra print cleaner at the forefront.

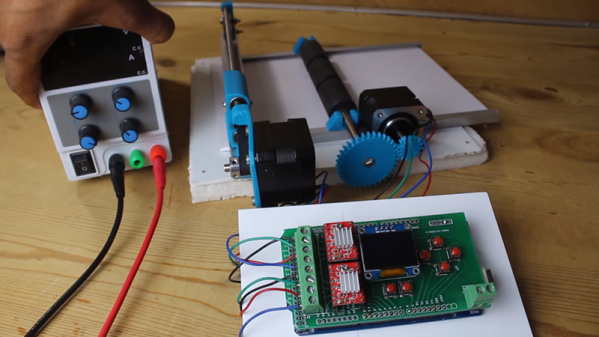

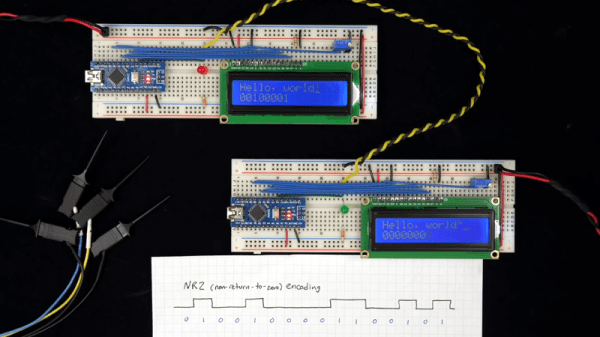

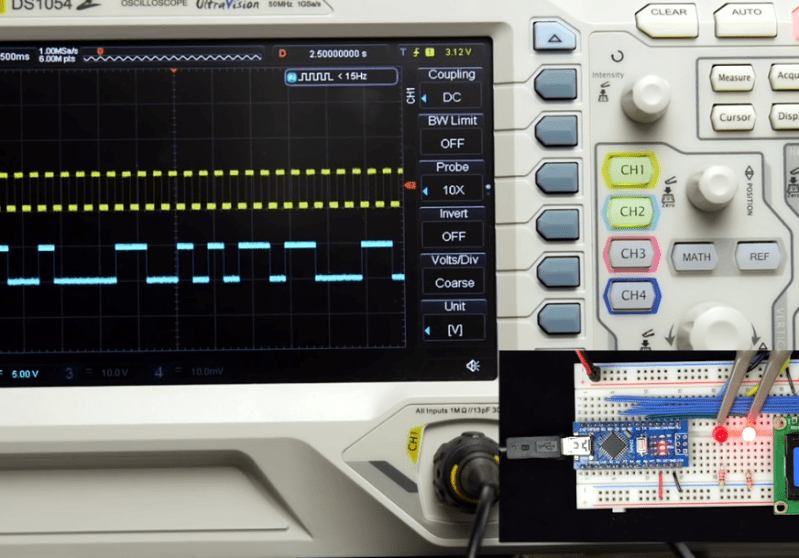

If you want to see more of his work, he has quite a few videos on his website demonstrating the before and after of the project — just make sure to bring a translator. He even has a handy pinout for those looking to replicate his work. If you want to dive right in to STM32 programming, we have a nice article on how to get it up and debugged. Otherwise, enjoy [Aaron Christophel]’s demonstration of the eight infra-red range sensors and the custom firmware running them.