This one goes out to anyone who loves music and feels it in their soul, but doesn’t necessarily understand it in their head. No instrument should stand in the way of expression, but it seems like they all do (except for maybe the kazoo).

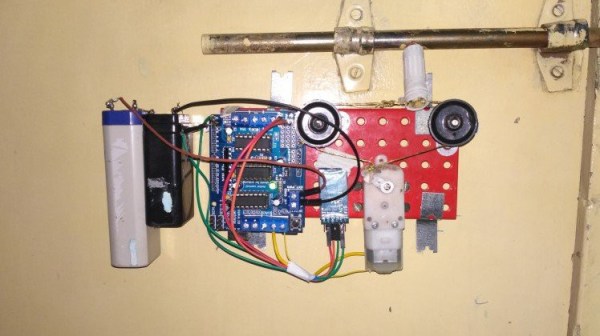

[FrancoMolina]’s hybrid synth-MIDI controller is a shortcut between the desire to play music and actually doing it. Essentially, you press one of the buttons along Synthfonio’s neck to set the scale, and play the actual notes by pressing limit switches in the controller mounted on the body. If you’re feeling blue, you can shift to minor scales by pressing the relative minor note’s neck button at the same time as the root note, e.g. A+C=Am. Want to change octaves? Just slide the entire controller up or down for a total of three.

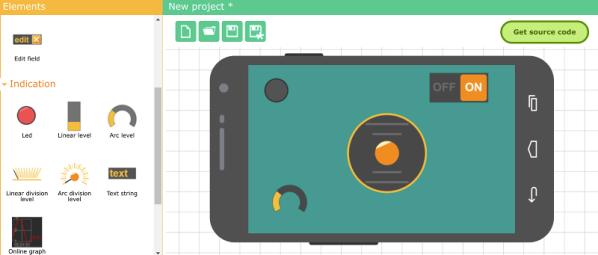

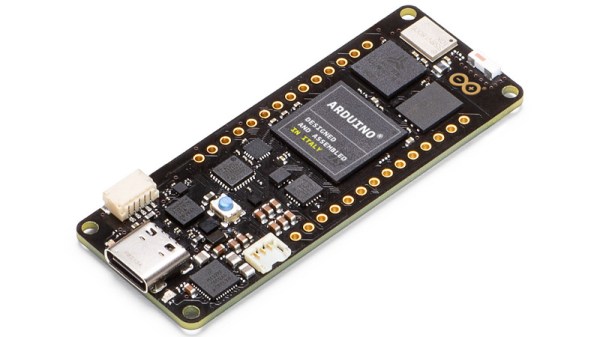

All of these switches are muxed to two Arduinos — an MKR1010 for USB MIDI control, and a bare ‘328 to provide the baked-in synth sounds. Power comes from a stepped-up 18650 that can be charged with an insanely cheap board from that one site. [Franco] has all the code and files available, so go have fun making music without being turned off by a bunch of theory. Push that button there to check out the demo.

If ‘portable’ means pocket-sized to you, then let this mini woodwind MIDI controller take your breath away.

Continue reading “Synthfonio Makes Music Easy Like Sunday Morning”