Plastic is a highly useful material, but one that can also be a pain as it ages. Owners of vintage equipment the world over are suffering, as knobs break off, bezels get cracked and parts warp, discolor and fail. Oftentimes, the strategy has been to rob good parts from other broken hardware and cross your fingers that the supply doesn’t dry up. [Eric Strebel] shows us that’s not the only solution – you can replicate vintage plastic parts yourself, with the right tools.

In the recording industry there’s simply no substitute for vintage gear, so a cottage industry has formed around keeping old hardware going. [Eric] was tasked with reproducing VU meter bezels for a classic Neve audio console, as replacement parts haven’t been produced since the 1970s.

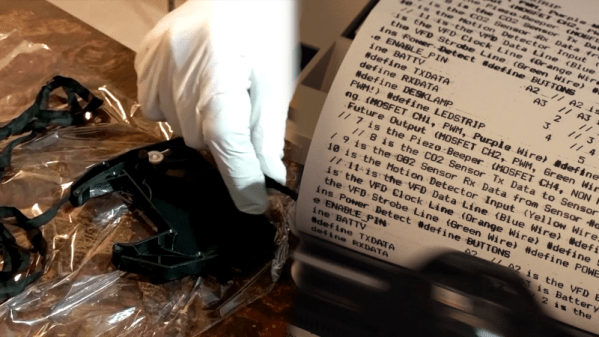

The first step is to secure a good quality master for replication. An original bezel is removed, and polished up to remove scratches and blemishes from 40+ years of wear and tear. A silicone mold is then created in a plywood box. Lasercut parts are used to create the base, runner, and vents quickly and easily. The mold is then filled with resin to produce the final part. [Eric] demonstrates the whole process, using a clear silicone and dyed resin to make it more visible for the viewer.

Initial results were unfortunately poor, due to the silicone and hardener used. The parts were usable dimensionally, but had a hazy surface finish giving very poor optical qualities. This was rectified by returning to a known-good silicone compound, which was able to produce perfectly clear parts first time. Impressively, the only finishing required is to snap off the runner and vents. The part is then ready for installation. As a final piece of showmanship, [Eric] then ships the parts in a custom laser-engraved cardboard case. As they say, presentation is everything.

With modern equipment, reproducing vintage parts like knobs and emblems is easier than ever. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Reproducing Vintage Plastic Parts In Top-Notch Quality”