For one reason or another, we’re going with a retro-futuristic 80s aesthetic in this case, [Mike] decided to turn an Apple IIe into a robot. If you have to ask why, you’ll never know, but this project does have some interesting things going for it. There’s a voice synthesizer, a brand spankin’ new power supply, and it rolls around on the floor thanks to Apple BASIC.

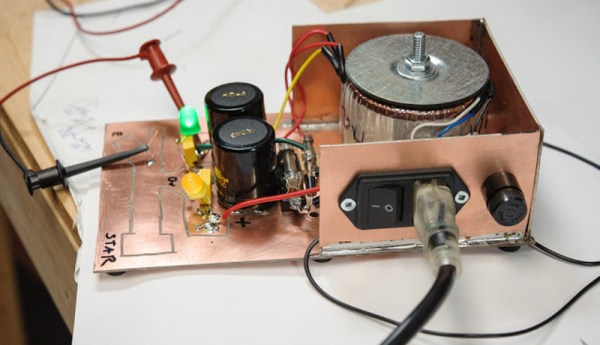

Since this is a mobile robot, there needs to be a power supply in there somewhere. The Apple II had a fantastic switching power supply, but it ran off mains voltage. To make this Apple run off a 14.8 V LiPO battery, [Mike] needed to re-engineer this power supply to give +5, +12, -5, and -12 Volts. The easiest is the positive voltage, and for that, he used a big ‘ol LM1084 linear regulator for the +5 V line. This outputs a ton of heat and probably isn’t the best solution, but it is a solution that works. The +12 line was again another linear regulator, an LM7812CV. Since this is dropping 14.8 V down to 12, the efficiency isn’t that bad, and since there’s no floppy drive it’s not pulling much current anyway. The negative voltages are a MAX764 / MAX765 inverting switching regulators. This completely replaces the original power supply in the Apple II, and is a decent reference design for anyone who wants to make a luggable Apple II laptop.

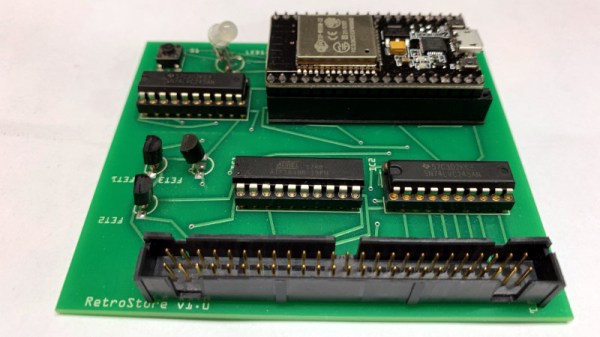

To move this thing around, the motors run on their own 11.1 V LiPO, with a bunch of Pololu gear tying everything together. The BASIC code was written on an emulator, transferred over with the Floppy Emu. Movement is controlled through the output pins on the joystick port, and there’s a text to speech module that was obviously needed and ties this project together wonderfully. You can check out the video demo of the build below.

Continue reading “Travelling The Oregon Trail With An Apple II Robot”