We sometimes forget that the things we think of as trivial today were yesterday’s feats of extreme engineering. Consider the humble pocket calculator, these days so cheap and easy to construct that they’re essentially disposable. But building a simple “four-banger” calculator in 1962 was anything but a simple task, and it’s worth looking at what one of the giants upon whose shoulders we stand today accomplished with practically nothing.

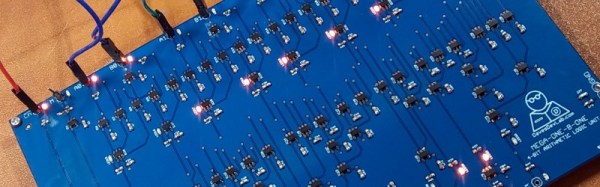

If there’s anything that [Cliff Stoll]’s enthusiasm can’t make interesting, we don’t know what it would be, and he certainly does the job with this teardown and analysis of a vintage electronic calculator. You’ll remember [Cliff] from his book The Cuckoo’s Egg, documenting his mid-80s computer sleuthing that exposed a gang of black-hat hackers working for the KGB. [Cliff] came upon a pair of Friden EC-132 electronic calculators, and with the help of [Bob Ragen], the engineer who designed them in 1962, got one working. With a rack of PC boards, cleverly hinged to save space and stuffed with germanium transistors, a CRT display, and an acoustic delay-line memory, the calculators look ridiculous by today’s standards. But when you take a moment to ponder just how much work went into such a thing, it really makes you wonder how the old timers ever brought a product to market.

As a side note, it’s great to see the [Cliff] is still so energetic after all these years. Watching him jump about with such excitement and passion really gets us charged up.