Ever wonder what’s inside an electrolytic capacitor? Many of us don’t, having had at least a partial glimpse inside after failure of the cap due to old age or crossed polarity. The rest of us will have to rely on this behind-the-scenes demo to find out what’s inside those little aluminum cans.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it’s more aluminum, at least for the electrolytics [Denki Otaku] rolled himself at the Nippon Chemi-Con R&D labs. Interestingly, both the anode and cathode start as identical strips of aluminum foil preprocessed with proprietary solutions to remove any oils and existing oxide layers. The strips then undergo electrolytic acid etching to create pits to greatly increase their surface area. The anode strips then get anodized in a solution of ammonium adipate, an organic acid that creates a thin aluminum oxide layer on the strip. It’s this oxide layer that actually acts as the dielectric in electrolytic capacitors, not the paper separator between the anode and cathode strips.

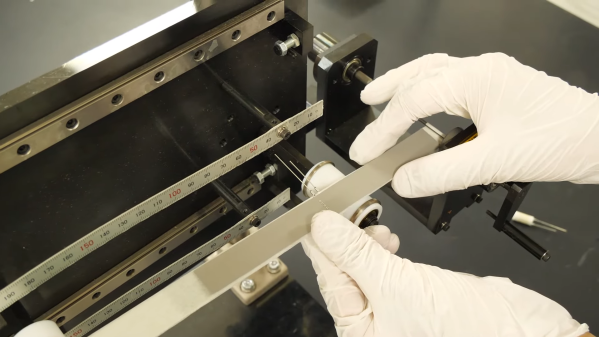

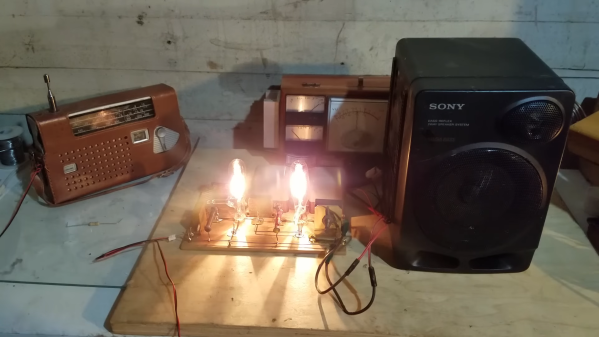

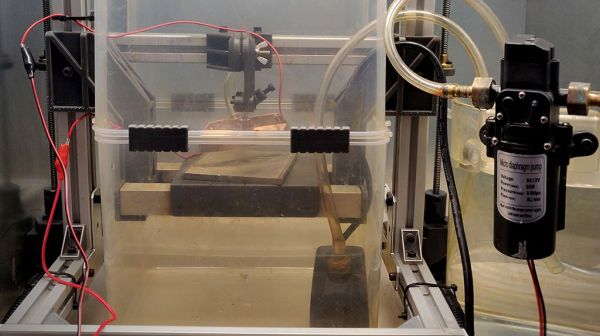

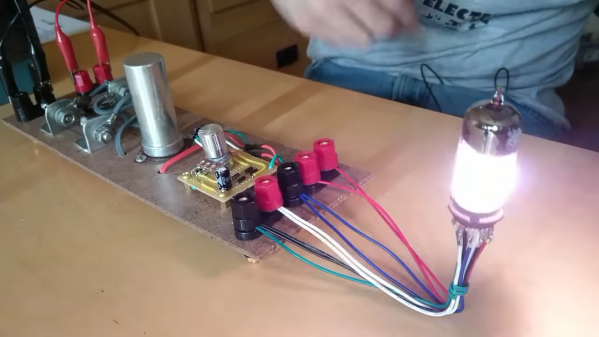

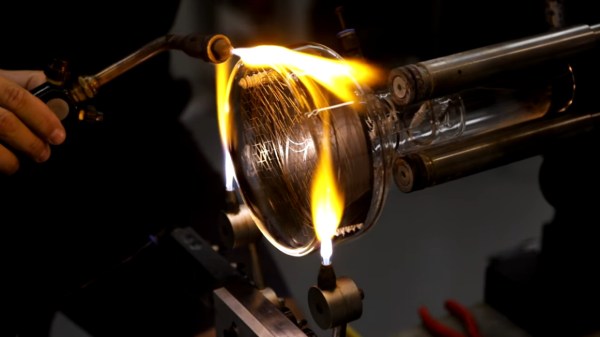

Winding the foils together with the paper separator is pretty straightforward, but there are some neat tricks even at the non-production level demonstrated here. Attachment of lead wires to the foil is through a punch and crimp operation, and winding the paper-foil sandwich is actually quite fussy, at least when done manually. No details are given on the composition of the electrolyte other than it contains a solvent and an organic acid. [Denki] took this as an invitation to bring along his own electrolyte: a bottle of Coke. The little jelly rolls get impregnated with electrolyte under vacuum, put into aluminum cans, crimped closed, and covered with a heat-shrink sleeve. Under test, [Denki]’s hand-rolled caps performed very well. Even the Coke-filled caps more or less hit the spec on capacitance; sadly, their ESR was way out of whack compared to the conventional electrolyte.

There are plenty more details in the video below, although you’ll have to pardon the AI voiceover as it tries to decide how to say words like “anode” and “dielectric”; it’s a small price to pay for such an interesting video. It’s a much-appreciated look at an area of the industry that few of us get to see in detail.

Continue reading “Learning About Capacitors By Rolling Your Own Electrolytics”