Slotting a modern media center into an old stereo usually means adding Bluetooth and a Raspberry Pi to an amp or receiver, and maybe adding a few discrete connectors on the back panel. But this media center for a late-70s Braun hi-fi (translated) goes many steps beyond that — it fabricates a component that never existed.

The article is in German, and the Google translation is a little spotty, but it’s pretty clear what [Sebastian Schwarzmeier] is going for here. The Braun Studio Line of audio components was pretty sleek, and to avoid disturbing the lines of his stack, he decided to create a completely new component and dub it the “M301.”

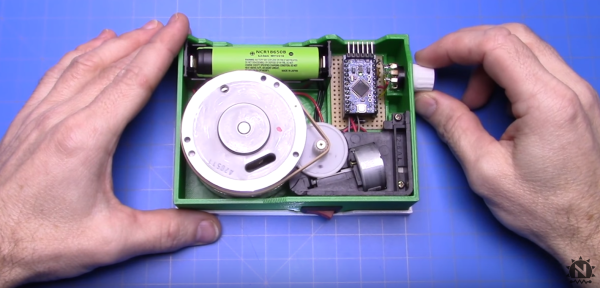

The gutted chassis of an existing but defunct A301 amplifier became the new home for a Mac Mini, Blu-Ray drive, and external hard drive. An HDMI port added to the back panel blends in with the original connectors seamlessly. But the breathtaking bit is a custom replacement hood that looks like what the Braun designers would have come up with if “media center” had been a term in the 70s.

From the brushed aluminum finish, to the controls, to the logo and lettering, everything about the component that never was shows an attention to detail that really impresses. But if you prefer racks of servers to racks of audio gear, this media center built into a server chassis is sure to please too.

Thanks to [Sascho] and [NoApple4Me] for the nearly simultaneous tips on this one.