A presentation this month by the Antique Wireless Museum brought British engineer and inventor John Sargrove (1906-1974) to our attention. If you’ve ever peeked inside old electronics from days gone by, you’ve no doubt seen point-to-point wiring and turret board construction. In the 60s and 70s these techniques eventually made way for printed circuit boards which we still use today. But Mr Sargrove was way ahead of his time, having already invented a process in the 1930s to print circuits, not just boards, onto Bakelite. After being interrupted by the war, he formed a company Electronic Circuit Making Equipment (ECME) and was building broadcast radio receivers on an impressive automatic production line.

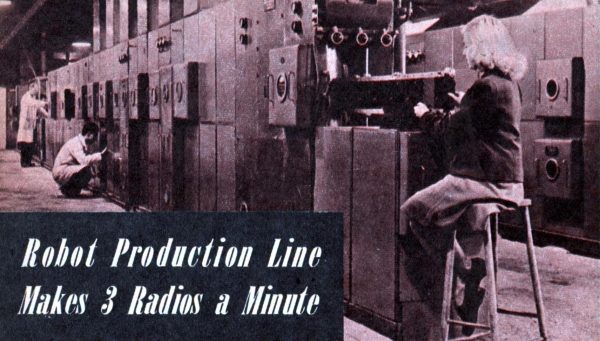

Mr. Sargrove’s passion was making radios affordable for everyone. But to achieve this goal, he had to make large advances manufacturing technology. His technique of embedding not only circuit traces, but basic circuit elements like resistors, capacitors, and inductors directly into the substrate foresaw techniques being applied decades later in integrated circuit design. He also developed a compact vacuum tube which could be used in all circuits of a radio, called an “All-stage Valve“. Equally important was his futuristic automatic factory, which significantly reduced the number of factory workers needed to make radios from 1500 to 50. Having completed the radio design, he was also developing a television receiver using the same concepts. Unfortunately, ECME was forced into liquidation when a large order from India was cancelled upon declaration of independence in 1947.

You really must watch the video below. There are many bits and pieces of modern factory automation which we still use today, yet their implementation using 1940s techniques and technology is fascinating. Further reading links after the video. Thanks to [Mark Erdle] for the tip.