The topic of energy has been top-of-mind for us since the first of our ancestors came down out of the trees looking for something to eat that wouldn’t eat them. But in a world where the neverending struggle for energy has been abstracted away to the flick of a finger on a light switch or thermostat, thanks to geopolitical forces many of us are now facing the wrath of winter with a completely different outlook on what it takes to stay warm.

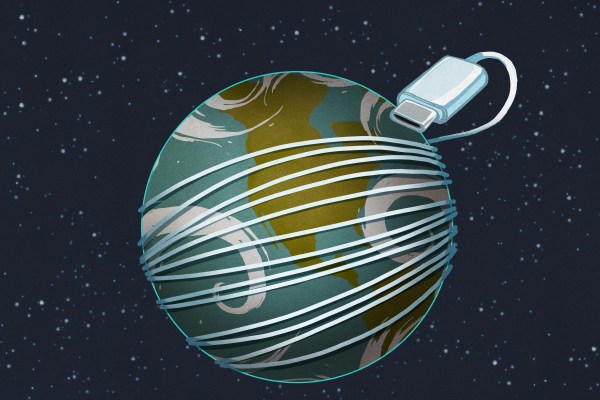

The problem isn’t necessarily that we don’t have enough energy, it’s more that what we have is neither evenly distributed nor easily obtained. Moving energy from where it’s produced to where it’s needed is rarely a simple matter, and often poses significant and interesting engineering challenges. This is especially true for sources of energy that don’t pack a lot of punch into a small space, like natural gas. Getting it across a continent is challenging enough; getting it across an ocean is another thing altogether, and that’s where liquefied natural gas, or LNG, comes into the picture.