Makerbot is in the gutter, 3D Systems and Stratasys stock is only a shadow of their 2014 glory, but this is the best year 3D printing has ever had. Machines are now good and cheap, there’s a variety of various thermoplastic filaments, and printing useful objects – instead of just plastic trinkets – is becoming commonplace.

There’s one area of 3D printing that hasn’t seen as much progress, and it’s the software stack. Slicing, the process of turning a 3D object into a Gcode file for a printer has been basically the same for the last few years. Dual extrusion is still a mess, and automated bed leveling is still in its infancy.

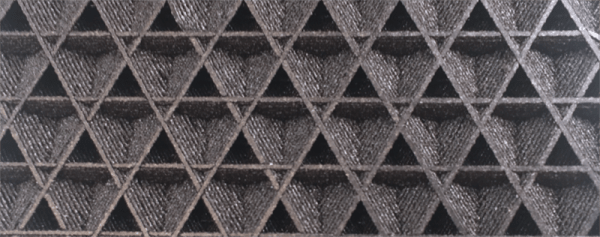

One aspect of slicing that has been severely overlooked is infill. Obviously, you don’t want to print plastic trinkets completely solid – only the outside surface matters, and a part with 100% infill is just a waste of plastic. Different slicers have come up with different ways of filling the inside of a print, usually with a grid of squares, triangles, or hexagons.

While the most popular methods of filling in a 3D printed objects do the job of adding a little bit of strength to a print and supporting the top layers of a print, it’s not an ideal solution. The desired strength of the finished part is never taken into account, print artifacts are sometimes visible through the side of a print, and the spacing of the infill grid is completely arbitrary. You can only set a percentage of infill, and telling a slicer to make an internal support grid with 10mm spacing is impossible.

Type A Machines just changed all of this. With the release of their public beta of Cura Type A, the infill for a 3D printed part is also 3D. The dimensions of the infill are predictable, opening the door to stronger and better looking parts.

From the Type A press literature and white paper, this new type of ‘infill’ isn’t; it’s more properly referred to as ‘internal structure’, with proper dimensions between infill features. Instead of a grid of squares or triangles stacked one layer on top of each other, it’s a true structure, with the infill following the perimeter of the 3D printed object.

Generating 3D Infill

Right now, infill is generated in a slicer by specifying a percentage. Zero percent infill means a hollow object, and 100% infill is a completely solid part. These two edge cases are easy, but anything else means the slicer must fill the part with filament in a grid of tessellating shapes, either rectangles, triangles, or hexagons. With current slicers, the dimensions of this internal structure are, for all practical purposes, random. Printing an object with 20% infill might mean a grid of squares with 5mm or 2mm spacing. Telling the slicer to infill a part with a grid of squares spaced 10mm apart is impossible.

Type A Machine’s latest Cura release changes all of this, allowing a designer to set a precise distance between rows and columns of infill. By defining infill in absolute dimensions, this allows for stronger parts using less infill.

Absolute dimensioning is only one feature of the Type A Machine’s latest release of Cura. Even more exciting is the development of 3D internal structure. Instead of stacking layers of squares, triangles, or hexagons on top of each other, Type A Machine’s Cura uses an infill of cubes turned on their side. While each individual layer of infill looks like a series of triangles and irregular hexagons, when assembled into a printed 3D object, this infill forms a true 3D structure.

The closest comparison to this sort of structure is the difference between graphite and diamond. Both of these materials are made out of the same element, carbon. The physical structure of graphite is just, 1-atom-thick layers of graphene, producing a relatively weak material. Diamond, on the other hand, has a true 3D structure and is one of the hardest materials known to man. While adding 3D structure to the infill of 3D printed objects won’t make the objects any stronger, it will drastically reduce delamination, and be much more resistant to stresses in all three dimensions.

While Type A Machines has done some great work here, it does mean there’s yet another version of Cura to deal with. Type A Machine’s Cura, in addition to the LulzBot edition and the original are now the defacto standard for turning 3D objects into printed parts. Having an open source solution is great, but forking the development this much surely can’t be ideal.