Everyone likes a good animated GIF, except for some Hackaday commenters who apparently prefer to live a joyless existence. And we can’t think of a better way to celebrate moving pictures than with a 3D printed trinocular camera that makes digital Wigglegrams a snap to create.

What’s a Wigglegram, you say? We’ve seen them before, but the basic idea is to take three separate photographs through three different lenses at the same time, so that the parallax error from each lens results in three slightly different perspectives. Stringing the three frames together as a GIF later results in an interesting illusion of depth and motion. According to [scealux], the inspiration for building this camera came from photographer [Kirby Gladstein]’s work, which we have to admit is pretty cool.

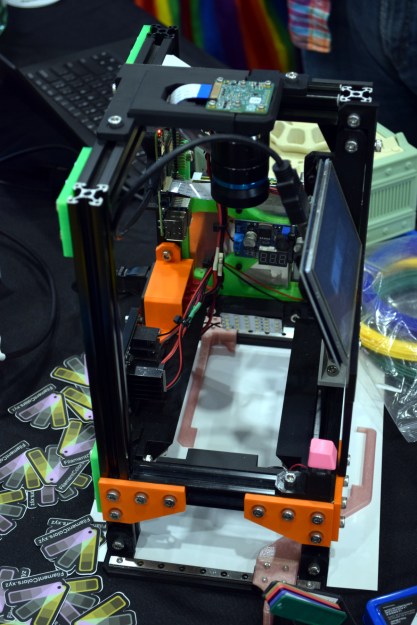

While [Kirby] uses a special lenticular film camera for her images, [scealux] decided to start his build with a Sony a6300 mirrorless digital camera. A 3D printed lens body with a focusing mechanism holds three small lenses which were harvested from disposable 35 mm film cameras — are those still a thing? Each lens sits in front of a set of baffles to control the light and ensure each of the three images falls on a distinct part of the camera’s image sensor.

The resulting trio of images shows significant vignetting, but that only adds to the charm of the finished GIF, which is created in Photoshop. That’s a manual and somewhat tedious process, but [scealux] says he has some macros to speed things up. Grainy though they may be, we like these Wigglegrams; we don’t even hate the vertical format. What we’d really like to see, though, is to see everything done in-camera. We’ve seen a GIF camera before, and while automating the post-processing would be a challenge, it seems feasible.

Continue reading “Trinocular Lens Makes Digital Wigglegrams Easier To Take”