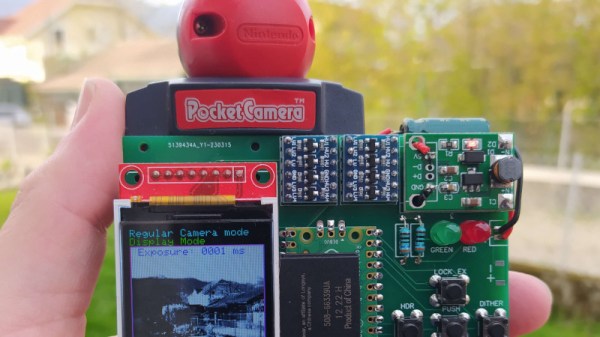

At least as far as the inner workings are concerned, there’s not a whole lot of difference between an single-lens reflex (SLR) camera that uses film and a digital SLR (DSLR) camera that uses an electronic sensor except the method for capturing the image. So adding the digital image sensor to a formerly analog camera like this seemed like an interesting project for [Wenting Zhang]. But this camera ballooned a little further than that as he found himself instead building a complete, full-frame digital camera nearly from scratch.

The camera uses a full-frame design and even though the project originally began around the SLR mechanism, in the end [Wenting] decided not to keep this complex system in place. Instead, to keep the design simple and more accessible a mirrorless design is used with an electronic viewfinder system. It’s also passive M lens mount, meaning that plenty of manual lenses will be available for this camera without having to completely re-invent the wheel.

As far as the sensor goes, [Wenting] wanted something relatively user-friendly with datasheets available so he turned to industrial cameras to find something suitable, settling on a Kodak charge-coupled device (CCD) for the sensor paired with an i.MX processor. All of the electronics have publicly-available datasheets which is important for this open-source design. There’s a lot more work that went into this build than just picking parts and 3D printing a case, though, and we’d definitely recommend anyone interested to check out the video below for how this was all done. And, for those who want to go back to the beginnings of this project and take a different path, it’s definitely possible to convert an analog SLR to a digital one.

Continue reading “SLR To DSLR Conversion Becomes Full Camera”

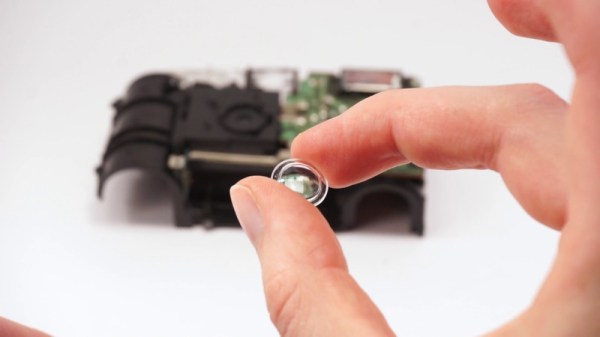

In building a new lens for the Open Sauce ’23 event, [scealux] wanted to get variable aperture working, while also improving focus speed. The lens was also intended for use with a Sony A7R3. Unlike his previous effort, this lens would only work on the full-frame Sony FE mount cameras.

In building a new lens for the Open Sauce ’23 event, [scealux] wanted to get variable aperture working, while also improving focus speed. The lens was also intended for use with a Sony A7R3. Unlike his previous effort, this lens would only work on the full-frame Sony FE mount cameras.