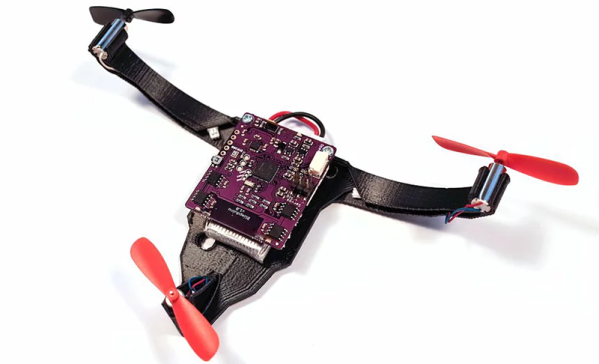

If you could pick a news story you would prefer not to be woken with, it’s likely that a major airport being closed due to a drone sighting would be high on the list. But that’s the news this morning: London’s Gatwick airport has spent most of the night and into the morning closed due to repeated sightings. Police are saying that the flights appear to have been deliberate, but not terror-related.

We’ve written on reports of drone near-misses with aircraft here back in 2016, and indeed we’ve even brought news of a previous runway closure at Gatwick. But it seems that this incident is of greater severity, over a much longer period, and even potentially involving more than one machine. The effect that it could have on those in our community who are multirotor fliers could be significant, and thus it is a huge concern aside from the potential for mishap in the skies above London’s second largest airport.

It is safe to say that if there was indeed a multirotor above Gatwick last night then its operator should be brought to justice and face the appropriate penalty without delay. Responsible fliers are painfully aware of the rules involving multirotor flight, and that airports of any description are strictly off-limits. It matters not whether this was a drunken prank or a premeditated crime, we hope you’ll all join us in saying that anybody flying outside the law should be reported to the authorities.

Continue reading “London Gatwick Airport Shuts Its Doors Due To Drone Sighting”