GPS is a handy modern gadget — until you go inside, underground, or underwater. Japanese researchers want to build a GPS-like system with a twist. It uses cosmic ray muons, which can easily penetrate buildings to create high-precision navigation systems. You can read about it in their recent paper. The technology goes by MUWNS or wireless muometric navigation system — quite a mouthful.

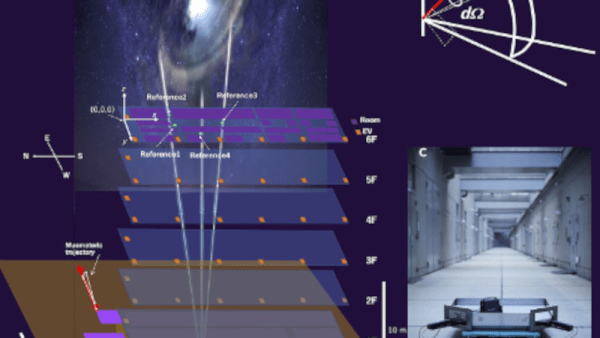

With GPS, satellites with well-known positions beam a signal that allows location determination. However, those signals are relatively weak radio waves. In this new technique, the reference points are also placed in well-understood positions, but instead of sending a signal, they detect cosmic rays and relay information about what it detects to receivers.

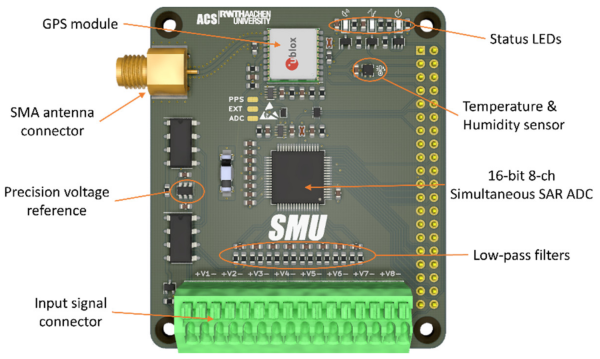

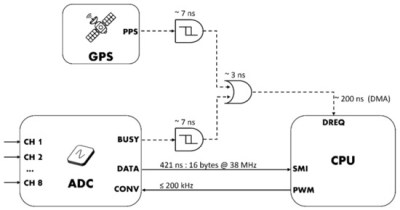

The receivers also pick up cosmic rays, and by determining the differences in detection, very precise navigation is possible. Like GPS, you need a well-synchronized clock and a way for the reference receivers to communicate with the receiver.

Muons penetrate deeper than other particles because of their greater mass. Cosmic rays form secondary muons in the atmosphere. About 10,000 muons reach every square meter of our planet at any minute. In reality, the cosmic ray impacts atoms in the atmosphere and creates pions which decay rapidly into muons. The muon lifetime is short, but time dilation means that a short life traveling at 99% of the speed of light seems much longer on Earth and this allows them to reach deep underground before they expire.

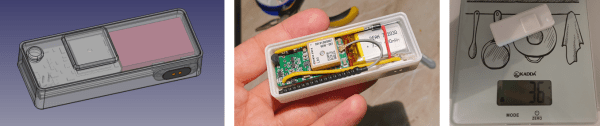

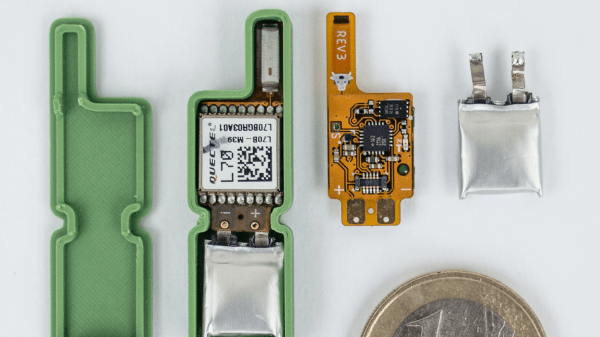

Detecting muons might not be as hard as you think. Even a Raspberry Pi can do it.