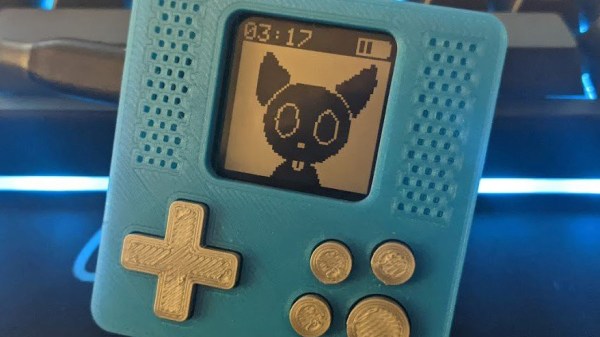

Browsing through the recent projects on Hackaday.io, we’ve found this entry by [NanoCodeBug]: a single-PCB low-power trinket reviving the “pocket pet” concept while having some fun in the process! Some serious thought was put into making this device be as low-power as possible – with a gorgeous Sharp memory LCD and a low-power-friendly SAMD21, it can run for two weeks on a pair of mere AAA batteries, and possibly more given a sufficiently polished firmware. The hardware has some serious potential, with the gadget’s platform lending itself equally well to Arduino or CircuitPython environments, the LCD being overclock-able to 30 FPS, mass storage support to enable pet transfer and other PC integrations, a buzzer for all of your sound needs, and an assortment of buttons to help you create mini-games never seen before. [NanoCodeBug] has been working on the hardware diligently for the past month, having gone through a fair few revisions – this is shaping up to be a very polished gadget!

There’s no wonder that people love to start Tamagotchi-like projects – something special happens when an electronic device invokes the same feelings that we’d get while caring for our own pet, and this project does justice to the idea. With homebrew Tamagotchi projects, there’s a trend – once hardware is finished, the software doesn’t always get to a usable stage, feeling more like an afterthought. There’s a hacker twist that should help us subvert this trend, however – [NanoCodeBug] has shared all sources with us in a GitHub repository! If you would like to help with the “software” part, you can start working on that with just a few breakouts. The board files are also there, if you feel like the boards are marvelous enough for your liking to go through modern-day component sourcing pains.

Hackers have been playing with the “pocket pet” concept here and there, to delightful and unconventional results. If you’re on the lookout for other serious Tamagotchi recreation projects, this one takes the cake – otherwise, check out this furry Tamagotchi-like Tribble pet, disarming in its cuteness! If you’re one of our mischief-minded hackers, we have two posts to keep you entertained – one about dumping ROM on newer Tamagotchi toys, and another about building a WiFi-cracking one. And when it comes to the spirit of “what we have on hand” builds, this giant desktop-sized LED matrix Tamagotchi fits the bill pretty well!