As we’ve seen with some recent posts on the subject here at Hackaday, there seems to be a growing schism within the community about the production of PCBs. Part of the community embraces (relatively) cheap professional fabrication, where you send your design off and get a stack of PCBs in the mail a couple weeks later. Others prefer at home methods of creating PCBs, such as using a CNC, laser engraver, or even the traditional toner transfer. These DIY PCBs take some skill and dedication to produce, but the advantage is that you can have the board in hand the same day you design it. But there may be a third option that seems to have slipped through the cracks.

[Virgil] writes in with a very interesting method of producing professional looking prototype PCBs that doesn’t involve weeks of waiting for the results, nor does it require any complicated techniques or specialized equipment. In this method, a UV printer is used to deposit your mask directly onto the copper clad board, which you then etch with whatever solution you like. Don’t have a UV printer you say? No worries, there’s probably somebody at the mall that does.

[Virgil] writes in with a very interesting method of producing professional looking prototype PCBs that doesn’t involve weeks of waiting for the results, nor does it require any complicated techniques or specialized equipment. In this method, a UV printer is used to deposit your mask directly onto the copper clad board, which you then etch with whatever solution you like. Don’t have a UV printer you say? No worries, there’s probably somebody at the mall that does.

As [Virgil] explains, the little kiosks at the mall which offer to personalize items for customers generally use a UV printer which allows them to shoot ink on nearly any material. Instead of asking them to put a logo on the back of your phone, you’ll just be asking them to put the vector file of your mask, which you can bring along on a USB flash drive, onto the bare copper board. They may tell you they can’t guarantee the ink will stick to the bare copper, but just tell them you’re willing to take the risk. It’s one of those situations in which your money will be glad to speak on your behalf.

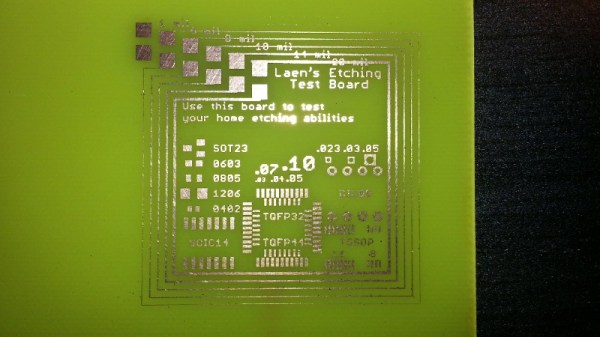

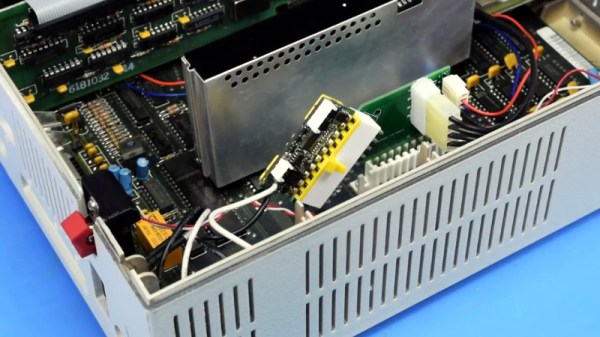

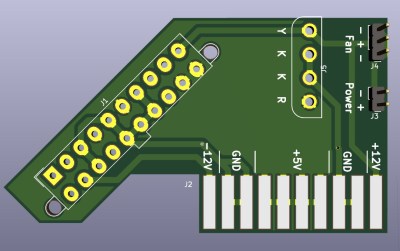

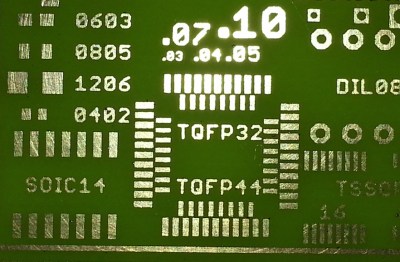

After the UV printer does its thing, the mask might be somewhat fragile. [Virgil] likes to wrap the boards in plastic for the ride home to make sure they don’t get damaged. Then it’s a quick dunk in the etching solution followed by a rinse and some isopropyl alcohol to get the remainder of the UV ink off. The results really do speak for themselves: nice sharp lines with exceptionally little manual work.

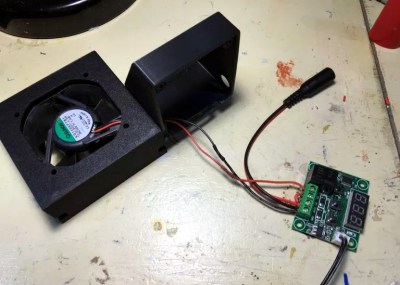

We’ve covered some relatively easy ways of quickly producing nice PCBs at home, as long as you don’t mind spending a couple hundred US dollars to get the hardware together. This seems to be the best of both worlds, though it does have the downside of requiring you speak with another human. We’d love to hear from any readers who give this particular method a shot.