To say that the RTL-SDR project revolutionized hacker’s capabilities in the RF spectrum would be something of an understatement. It used to be that the bar, in terms of both knowledge and hardware, was so high that only those truly dedicated were able to explore the radio spectrum. But today anyone with $20 can pick up an RTL-SDR device, combine it with a wide array of open source software, and gain access to a previously invisible world.

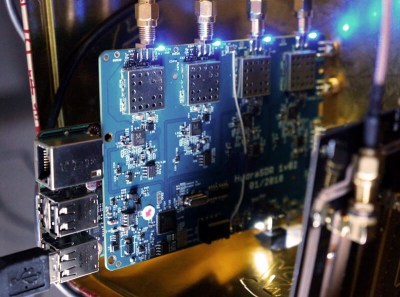

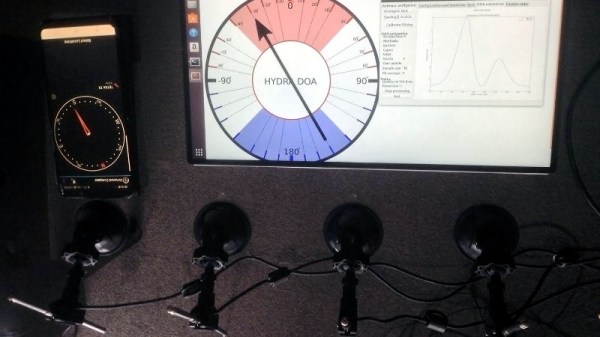

That being said, RTL-SDR is usually considered an “Economy Ticket” to the world of RF. It gets your foot in the door, but experienced RF hackers are quick to point out you’ll need higher-end hardware if you want to start doing more complex experiments. But the KerberosSDR may soon change the perception of RTL-SDR derived hardware. Combining four R820T2 SDRs on a custom designed board, it allows for low-cost access to high concept technologies such as radio direction finding, passive radar, and beam forming. If you get bored with that, you can always just use it as you would four separate RTL-SDR dongles, perfect for applications that require monitoring multiple frequencies such as receiving trunked radio.

That being said, RTL-SDR is usually considered an “Economy Ticket” to the world of RF. It gets your foot in the door, but experienced RF hackers are quick to point out you’ll need higher-end hardware if you want to start doing more complex experiments. But the KerberosSDR may soon change the perception of RTL-SDR derived hardware. Combining four R820T2 SDRs on a custom designed board, it allows for low-cost access to high concept technologies such as radio direction finding, passive radar, and beam forming. If you get bored with that, you can always just use it as you would four separate RTL-SDR dongles, perfect for applications that require monitoring multiple frequencies such as receiving trunked radio.

KerberosSDR (which was previously known as HydraSDR) is a collaborative effort between the Othernet engineering team and the folks over at RTL-SDR.com, who earlier in the year put out a call for an experienced developer to come onboard specifically for this project. Tamás Peto, a PhD student at Budapest University of Technology and Economics, answered the call and has put together a system which the team plans on releasing as open source so the whole community can benefit from it. In the videos after the break, you can see demonstrations of the direction finding and passive radar capabilities using an in-development version of KerberosSDR.

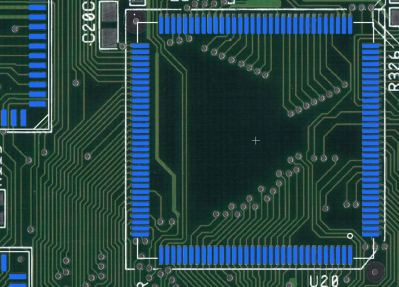

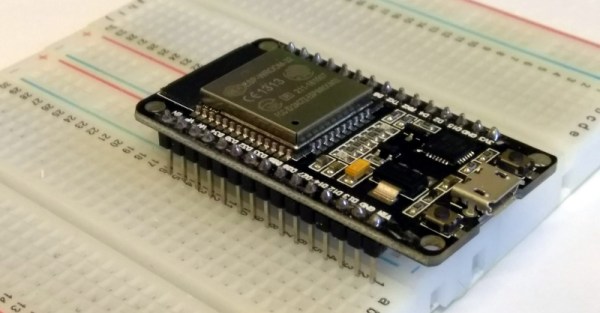

As for the hardware, it’s a combination of the RTL-SDR radios with an onboard GPIO-controlled wide band noise source for calibration, as well as an integrated USB hub so it only takes up one port. Everything is wrapped up in a shielded metal enclosure, and the team is currently experimenting with a header on the KerberosSDR PCB that would let you plug it directly into a Raspberry Pi or Tinkerboard.

The team hopes to start final hardware production within the next few months, and in the meantime has set up a mailing list so interested parties can stay in the loop and be informed when preorders start.

If you can’t wait until then, we’ve got a detailed write-up on DIY experiments with passive radar using RTL-SDR hardware, and you can always use your browser if you want to get your radio direction finding fix.

Continue reading “Direction Finding And Passive Radar With RTL-SDR”

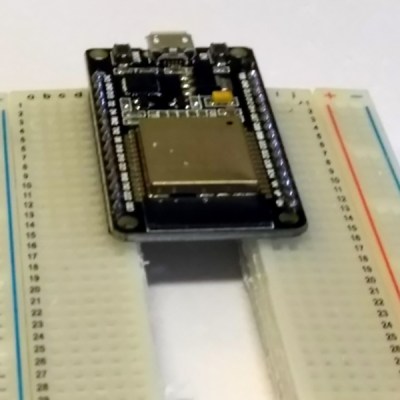

The solution came to [Luc] when he realized the center of every breadboard has no electrical connections, and was simply held together by a little piece of plastic. Yes, he took a hacksaw to the breadboard. This is technically a hack.

The solution came to [Luc] when he realized the center of every breadboard has no electrical connections, and was simply held together by a little piece of plastic. Yes, he took a hacksaw to the breadboard. This is technically a hack.