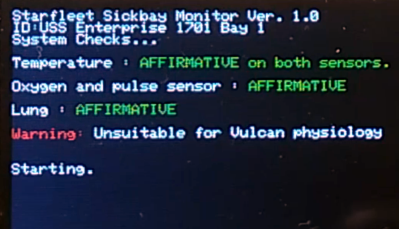

The various displays and interfaces in Star Trek, especially The Original Series, were intentionally designed to be obtuse and overly complex so they would appear futuristic to the audience. If you can figure out how Sulu was able to fly the Enterprise with an array of unlabeled buttons and rocker switches, we’d love to hear it. But one area of the ship where this abstract design aesthetic was backed off a bit was sickbay, as presumably they wanted the audience to be able to understand at a glance whether or not Kirk or Spock were going to pull through their latest brush with death (spoilers: they’re fine).

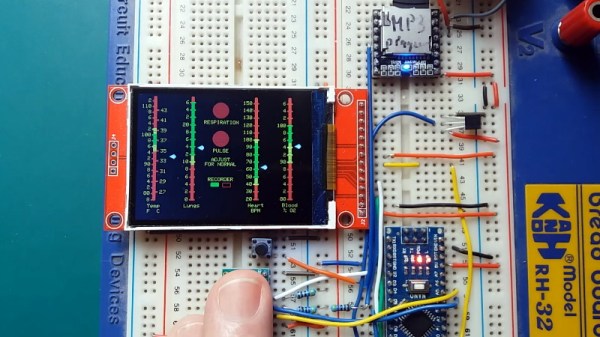

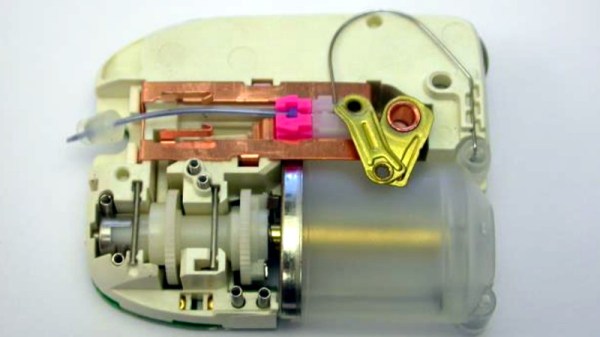

For his latest project, [XTronical] has recreated the classic displays from Dr McCoy’s sickbay with an Arduino Nano and a 2.8 inch LCD display. It even has a speaker and MP3 player module to recreate the “heartbeat” sound from the original show. The whole thing looks and sounds phenomenal, and would be a perfect desk toy for the classic Trek aficionado. But this isn’t just a toy, it’s a fully functional medical scanner.

For his latest project, [XTronical] has recreated the classic displays from Dr McCoy’s sickbay with an Arduino Nano and a 2.8 inch LCD display. It even has a speaker and MP3 player module to recreate the “heartbeat” sound from the original show. The whole thing looks and sounds phenomenal, and would be a perfect desk toy for the classic Trek aficionado. But this isn’t just a toy, it’s a fully functional medical scanner.

Of course, this little gadget can’t tell you if you’ve come down with a nasty case of Rigellian fever, but it can read your vitals using a MAX30100 pulse oximeter module and DS18B20 thermometer. In fact, it actually has two DS18B20 sensors: one to measure ambient temperature, the other to measure skin temperature. With those two figures, [XTronical] says it can calculate your core body temperature. The only thing that’s made up is the blinking “Respiration” indicator, that one’s just an estimate.

So where do we go from here? This project is presented as merely the first step in building a complete prop, perhaps in the form of a medical tricorder. We’ve seen some phenomenal TOS tricorder builds over the years, and some have even used the Raspberry Pi to shoehorn a bit of functionality into them. [XTronical] says he’s working on getting the source code and a step-by-step build guide put together, so keep an eye out for that in the near future.

Continue reading “An Arduino Sickbay Display Worthy Of The Enterprise”