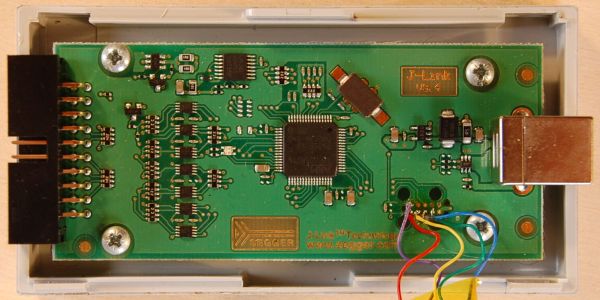

Last year [Emil] found themselves in the situation where a SEGGER J-link debug probe suddenly just stopped working. This was awkward not only because in-circuit debuggers are vital pieces of equipment in embedded firmware development, but also because they’re not that cheap. This led [Emil] to take the device apart to figure out what was wrong with it.

After checking voltages on the PCB, nothing obvious seemed wrong. The Tag-Connect style JTAG header on the PCB appeared to be a good second stop, requiring only a bit of work to reverse-engineer the exact pinout and hook up an ST-Link V2 in-circuit debugger to talk with the STM32F205RC MCU on the PCB. This led to the interesting discovery that apparently the MCU’s Flash ROM had seemingly lost the firmware data.

Fortunately [Emil] was able to flash back a version of the firmware which was available on the internet, allowing the J-Link device to work again. This was not the end of the story, however, as after this the SEGGER software was unable to update the firmware on the device, due to a missing bootloader that was not part of the firmware image.

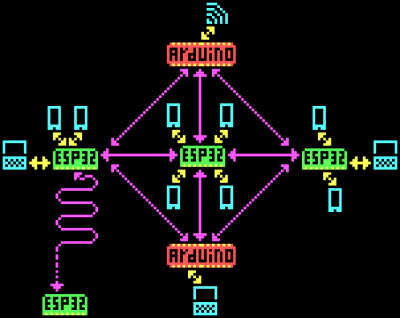

Digging further into this, [Emil] found out a whole host of fascinating details about not only these SEGGER J-Link devices, but also the many clones that are out there, as well as the interesting ways that SEGGER makes people buy new versions of their debug probes.

(Thanks Zelea for the tip)