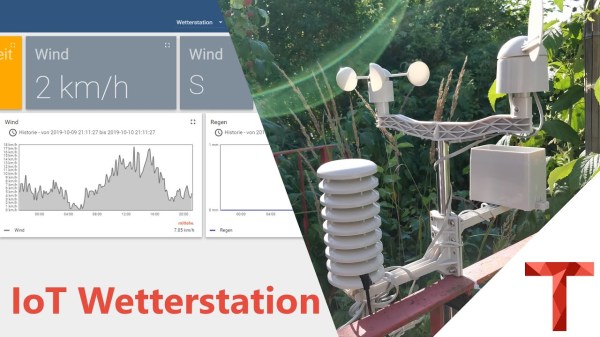

Weather stations are a popular project, partly because it’s helpful (and interesting) to know about the weather at your exact location rather than a forecast that might be vaguely in your zip code. They’re also popular because they’re a good way to get experience with microcontrollers, sensors, I/O, and communications protocols. Your own build may also be easily upgradeable as the years go by, and [Tysonpower] shows us some of the upgrades he’s made to the popular Sparkfun weather station from a few years ago.

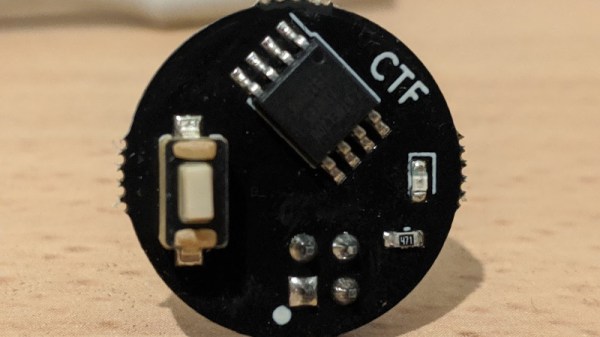

The Sparkfun station is a good basis for a build though, it just needs some updates. The first was that the sensor package isn’t readily available though, but some hunting on Aliexpress netted a similar set of sensors from China. A Wemos D1 Mini was used as a replacement controller, and with it all buttoned up and programmed it turns out to be slightly cheaper (and more up-to-date) than the original Sparkfun station.

All of the parts and code for this new station are available on [Tysonpower]’s Github page, and if you want to take a look at a similar station that we’ve featured here before, there’s one from three years ago that’s also solar-powered.

Continue reading “Weather Station Gets Much-Needed Upgrades”