Why would anyone put as much effort into resurrecting a 1970s split-flap clock as [mitxela] did when he built this custom PLL frequency converter? We’re not sure, but we do like the results.

The clock is a recreation of the prop from the classic 1993 film, Groundhog Day, rigged to play nothing but “I Got You Babe” using the usual sound boards and such. But the interesting part was getting the clock mechanism keeping decent time. Sourced from the US, the clock wanted 120 VAC at 60 Hz rather than the 240 VAC, 50 Hz UK standard. The voltage difference could be easily handled, but the frequency mismatch left the clock running unacceptably slow.

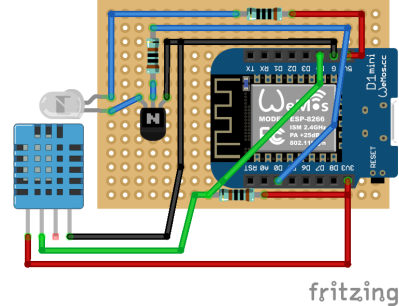

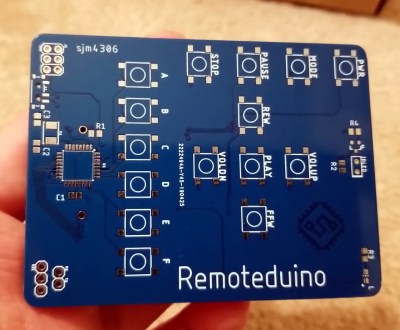

That’s when [mitxela] went all in and designed a custom circuit to convert the 50 Hz mains to 60 Hz. What’s more, he decided to lock his synthesized waveform to the supply current, to take advantage of the long-term frequency control power producers are known for. The write-up goes into great detail about the design of the phase-locked loop (PLL), which uses an ATtiny85 to monitor the rising edge of the mains supply and generate the PWM signal that results in six cycles out for every five cycles in. The result is that the clock keeps decent time now, and he learned a little something too.

If the name [mitxela] seems familiar, it’s probably because we’ve featured many of his awesome builds before. From ludicrous-scale soldering to a thermal printer Polaroid to a Morse-to-USB keyboard, he’s always got something cool going on.