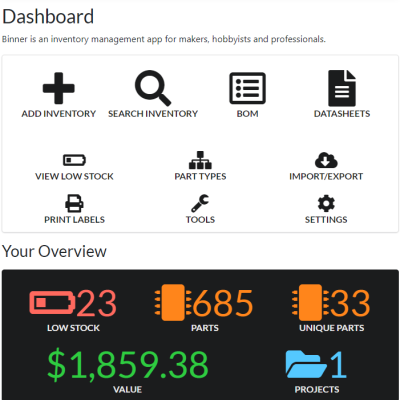

We’ve all had times where we knew we had some part but we had to go searching for it all over as it wasn’t where we thought we put it. Organizing the numerous components, parts, and supplies that go into your projects can be a daunting task, especially if you use the same type of part at different times for different projects. It helps to have a framework to keep track of all the small details. Binner is an open source project that aims to allow you to easily maintain a database that can be customized to your use.

In a recent video for DigiKey, [Byte Sized Engineer] used Binner to track the locations of his components and parts in his freshly organized workshop. Binner already has the ability to read the labels used by well-known electronics suppliers via a barcode scanner, and uses that information to populate your inventory. It even grabs quantities and links in a datasheet for your newly added part. The barcode scanner can also be used to retrieve the contents of a location, so with a single scan Binner can bring up everything residing at that location.

In a recent video for DigiKey, [Byte Sized Engineer] used Binner to track the locations of his components and parts in his freshly organized workshop. Binner already has the ability to read the labels used by well-known electronics suppliers via a barcode scanner, and uses that information to populate your inventory. It even grabs quantities and links in a datasheet for your newly added part. The barcode scanner can also be used to retrieve the contents of a location, so with a single scan Binner can bring up everything residing at that location.

Binner can be run locally so there isn’t the concern of putting in all the effort to build up your database just to have an internet outage make it inaccessible. Another cool feature is that it allows you to print labels, you can customize the fields to display the values you care about.

The project already has future plans to tie into a “smart bin” system to light up the location of your component — a clever feature we’ve seen implemented in previous setups.

Continue reading “Binner Makes Workshop Parts Organization Easy”