If you don’t know what a print processor is, don’t feel bad. There’s precious few people out there still running home darkrooms, and the equipment used for DIY film development is about as niche as it gets today. For those looking to put together their own darkroom in 2019, buying second hand hardware and figuring out how to fix it on your own is the name of the game, as [Austin Robert Hermann] found out when he recently purchased a Durst Printo Print Processor on eBay.

The auction said the hardware was in working order, but despite the fact that nobody would ever lie on the Internet, it ended up being in quite poor condition. Many of the gears in the machine were broken, and some were simply missing. The company no longer supports these 1990’s era machines, and the replacement parts available online were predictably expensive. [Austin] determined his best course of action was to try his hand at modeling the necessary gears and having them 3D printed; two things he had no previous experience with.

The auction said the hardware was in working order, but despite the fact that nobody would ever lie on the Internet, it ended up being in quite poor condition. Many of the gears in the machine were broken, and some were simply missing. The company no longer supports these 1990’s era machines, and the replacement parts available online were predictably expensive. [Austin] determined his best course of action was to try his hand at modeling the necessary gears and having them 3D printed; two things he had no previous experience with.

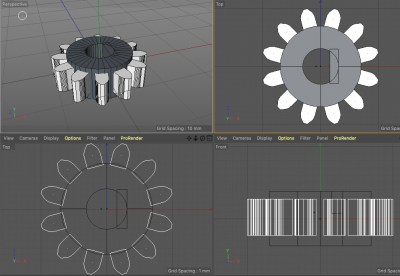

Luckily for [Austin], many of the gears in the Printo appeared to be identical. That meant he had several intact examples to base his 3D models on, and with some educated guesses, was able to determine what the missing gears would have looked like. Coming from an animation background, he ended up using Cinema 4D to model his replacement parts; which certainly wouldn’t have been our first choice, but there’s something to be said for using what you’re comfortable with. Software selection not withstanding, he was able to produce some valid STLs which he had printed locally in PLA using an online service.

Interestingly, this is a story we’ve seen play out several times already. Gears break and wear down, and for vintage hardware, that can be a serious problem. But if you’ve got a couple intact gears to go by, producing replacements even on an entry level desktop 3D printer is now a viable option to keep these classic machines running.