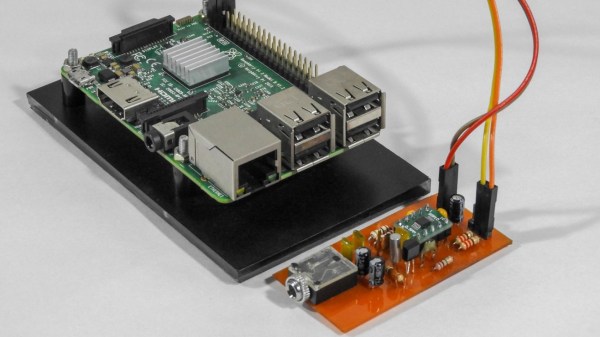

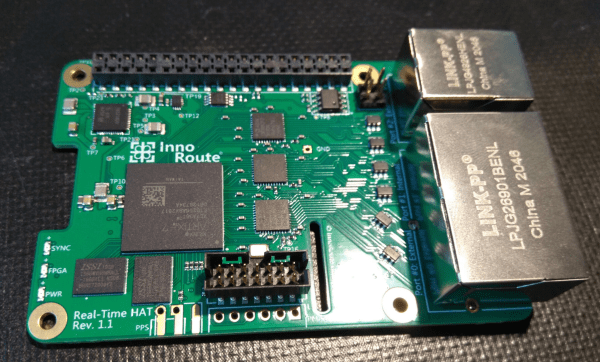

The new Real-Time HAT by InnoRoute adds IEEE1588 PTP support in hardware to a Raspberry Pi 4 nestled beneath. Based around a Xilinx Artix-7 FPGA and a handful of gigabit Ethernet PHY devices, the HAT acts as network-passthrough, adding accurate time-stamps to egress (outgoing) packets and stripping time-stamps from the ingress (incoming) side.

This hardware time-stamping involves re-writing Ethernet packets on-the-fly using specialised network hardware which the Raspberry Pi does not have. Yes, there are software-only 1588 stacks, but they can only get down to 10s of microsecond resolutions, unlike a hardware approach which can get down to 10s of nanoseconds.

1588 is used heavily for applications such as telecoms infrastructure, factory equipment control and anything requiring synchronisation of data-consuming or data-producing devices. CERN makes very heavy use of 1588 for its enormous arrays of sensors and control equipment, for all the LHC experiments. This is the WhiteRabbit System, presumably named after the time-obsessed white rabbit of Alice In Wonderland fame. So, if you have a large installation and a need for precisely controlling when stuff happens across it, this may be just the thing you’re looking for.

IEEE1588 PTP Synchronisation

The PTP client and master device ping a few messages back and forth between themselves, with the network time-stamper recording the precise moment a packet crosses the interface. These time-stamps are recorded with the local clock. This is important. From these measurements, the time-of-flight of the packet and offset of the local clock from the remote clock may be calculated and corrected for. In this way each client node (the hat) in the network will have the same idea of current time, and hence all network packets flowing through the whole network can be synchronised.

The beauty of the system is that the network switches, wiring and all that common infrastructure don’t need to speak 1588 nor have any other special features, they just need to pass along the packets, ideally with a consistent delay.

The Real-Time HAT configures its FPGA via SPI, straight from Raspberry Pi OS, with multiple applications possible, just by a change on the command line. It is possible to upload custom bitstreams, allowing the HAT to be used as a general purpose FPGA dev board should you wish to do so. It even stacks with the official PoE HAT, which makes it even more useful for hanging sensors on the end of a single wire.

Of course, if your needs are somewhat simpler and smaller in scale than a Swiss city, you could just hack a GPS clock source into a Raspberry Pi with a little soldering and call it a day.