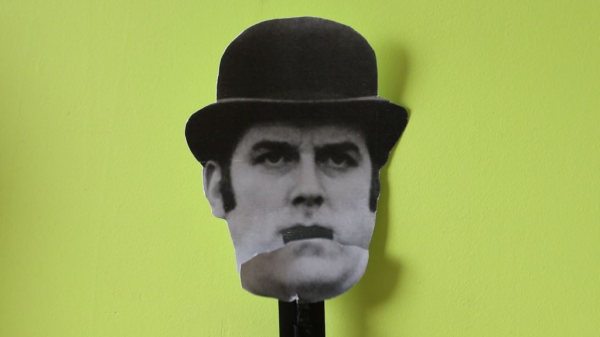

While in-person arguments are getting harder to come by these days, we’ll always have the internet (hopefully). So what can you do to stay on your game in a time when a little levity is lauded? Build an argument bot and battle wits with the best — a stern-faced John Cleese!

This latest offering from [8 Bits And A Byte] refers to a Monty Python sketch featuring an argument service — an office with a receptionist who will take your money and send you down the hall for a healthy and heated discussion. If you’ve never gone on a Monty Python binge, well, it’s probably as good a time as any.

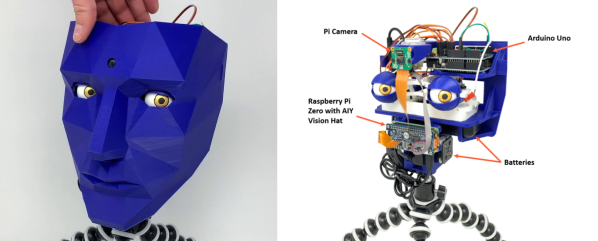

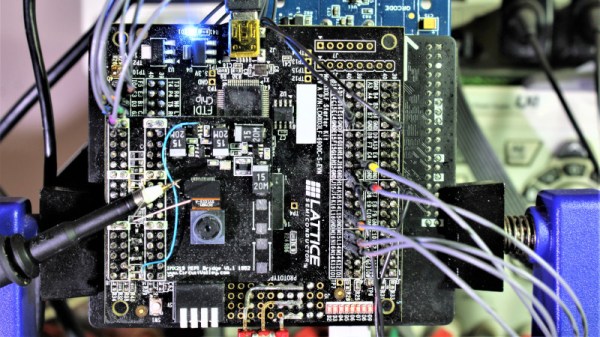

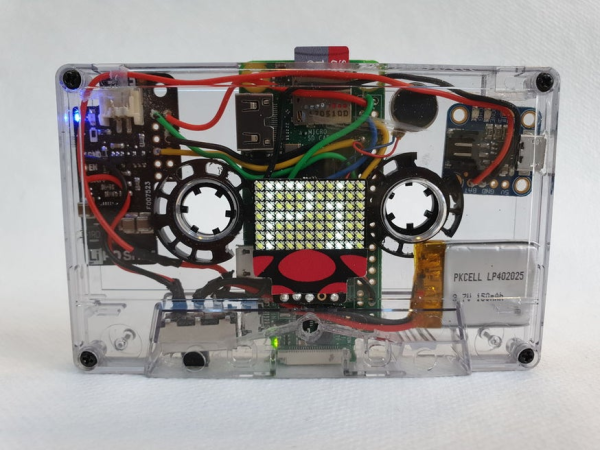

Electronics-wise, the argument bot is a pretty simple build. A Raspberry Pi B+ outfitted with a Google AIY hat listens to your side of things and decides which bones to pick. Your obviously misguided statements are then matched with DialogFlow intents, and dissent is sent back through the speaker. Meanwhile, Mr. Cleese’s jaw moves up and down on a printed and servo-driven linear actuator while he maintains a stiff upper lip. Before you go off on that Python binge, check out the build video after the break.

Have you seen what can happen two robots argue? ‘Tis but a scratch. Continue reading “This Is Not An Argument Bot”