Restoring a vintage radio receiver has the potential to be a fun weekend project, but it pays to know what you’re up against. Especially in the case of vacuum tube electronics, running down gremlins in the circuits isn’t always a straightforward process (also, please mind the high voltage that is present in old vacuum tube equipment). [Mr Carlson] has a knack for getting old radios humming once again, and his repair of a 1960s General Electric barn find radio receiver is a thorough masterclass in vintage electronics servicing.

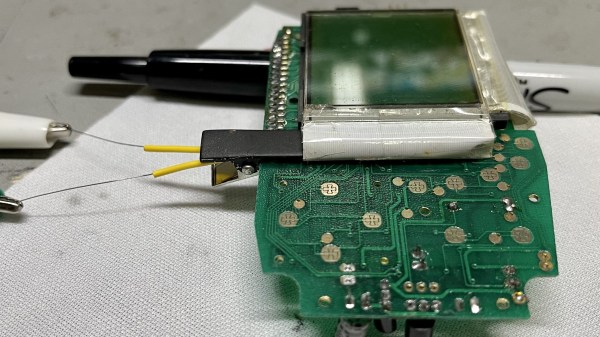

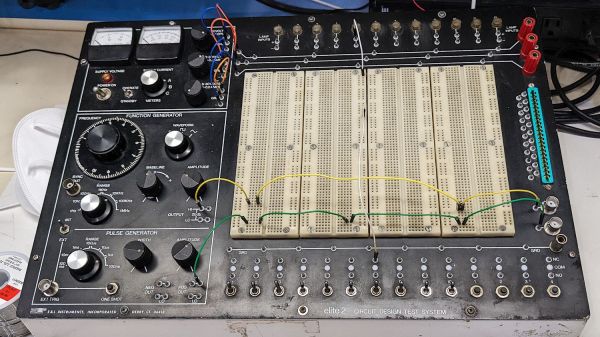

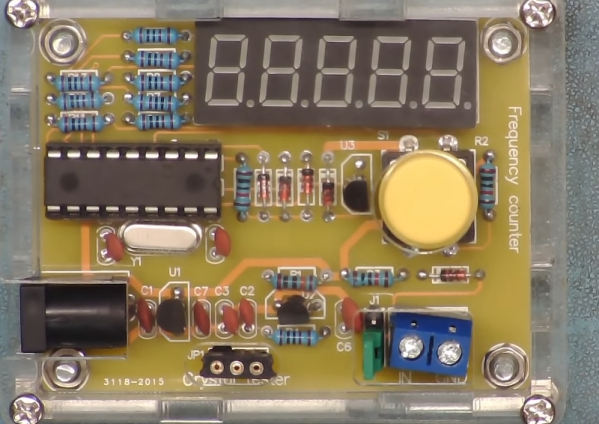

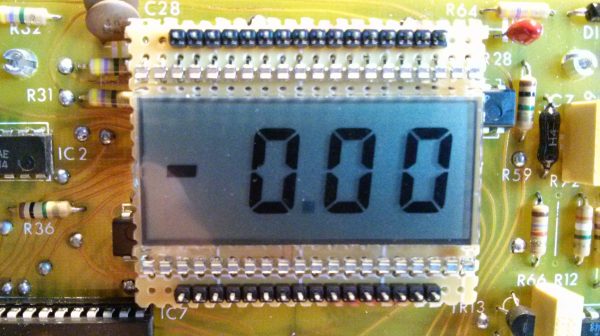

Seriously, if you’ve got a spare ninety minutes, the video (after the break) is a thorough and unabridged start-to-finish diagnosis and repair of a vintage radio, and an absolute must for anyone interested in doing the same. This barn find radio was certainly showing its age, and it wasn’t long before in-circuit testing found an open filament in one of several vacuum tubes, but the radio was still stubbornly silent. Further testing revealed that the IF transformers were out of spec, requiring servicing and alignment. After fine tuning both the IF and RF sections of the radio, things were definitely looking (and sounding) better.

Fine tuning the various components in the radio went a long way to living up to its “long range” claims, and by the end of the video, it’s almost impossible to find dead air on the AM dial of this radio. If you’ve never had to make fine adjustments to a receiver, especially of this vintage, this video has all the details you’ll need. With the board exposed, [Mr Carlson] also took care of some preventative maintenance, including replacing the original filter capacitor with newer components, as well as replacing the mains safety capacitor with an even safer modern alternative.

We can’t get enough of these restorations, so make sure to check out our detailed write-up of restoring a WWII aircraft radio.

Continue reading “Busted 1960s Vacuum Tube Radio Sings Again”