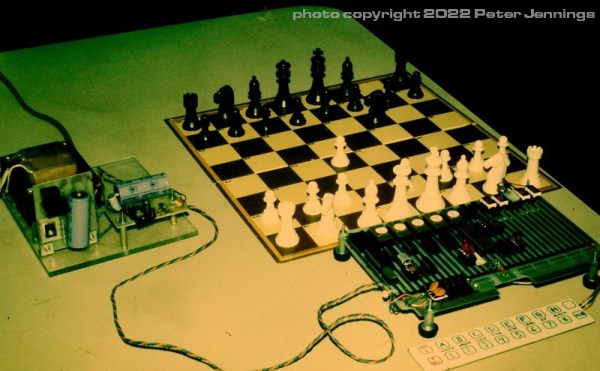

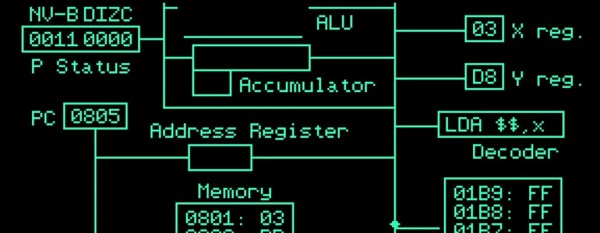

The Commodore International of the 1970s was a company which dabbled in a bit of everything when it came to consumer electronics, with the Commodore ChessMate being a prime example of the circuitous way that some of its products came to be. Released in 1978, its existence was essentially the result of MOS Technology releasing the KIM-1 single board computer in 1976. In May of that year, [Peter Jennings] traveled all the way from Toronto, Canada to Cleveland, USA to attend the Midwest Regional Computer Conference and acquire a KIM-1 system and box of manuals for a mere $245. On this KIM-1 he’d proceed to develop his own chess game, called MicroChess, implemented fully in 6502 ASM to fit within the 1 kB of RAM.

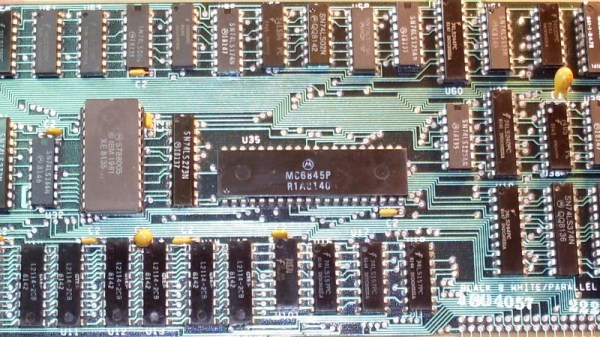

As one of the first major applications to run on the KIM-1, it quickly became an international hit, which caught the attention of Commodore – which had acquired MOS Technology by then – who ended up contacting [Peter] about a potential chess computer project. This turned out to based on the custom MOS 6504 CPU, while sharing many characteristics with the KIM-1 SBC. Being a MicroChess-only system, the user experience was optimized for more casual users, with the user manual providing clear instructions on how to start a new game and how to enter the position of a newly moved piece, along with no less than eight difficulty settings.

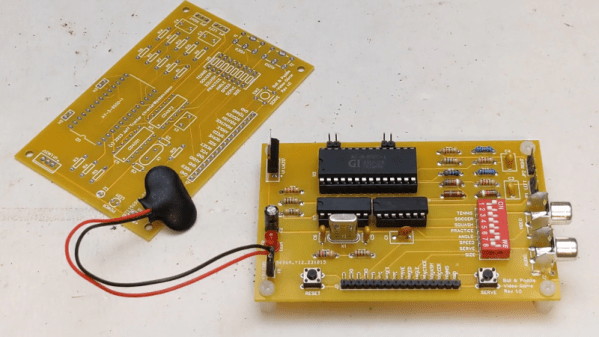

If you’re feeling like making your own ChessMate, or want to dig into the technical details, this excellent article by [Hans Otten] has got you covered.

Top image: Commodore ChessMate Prototype in 1978. (Credit: Peter Jennings)

(Thanks to [Stephen Walters] for the tip)