Table service and McDonalds sound as though they should be mutually exclusive as a fundamental of the giant chain’s fast food business model, but in many restaurants there’s the option of keying in the number from a plastic beacon when you order, placing the beacon on the table, and waiting for a staff member to bring your food. How does the system work? [Whiterose Infosec] scored one of the beacons, and subjected it to a teardown and some probing.

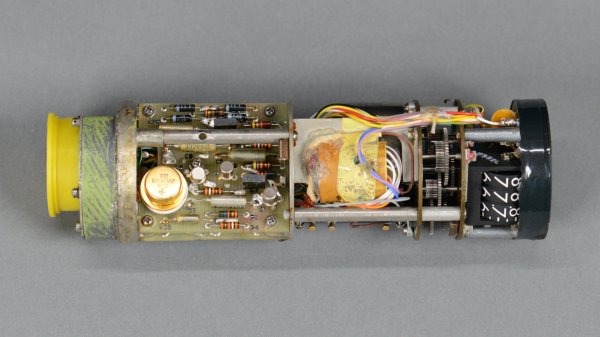

The beacon in question has the look of being an older model judging by the 2009 date codes on its radio module and the evident corrosion on its battery terminals. Its Bluetooth 4 SoC is end-of-life, so it’s possible that this represents a previous version of the system. It has a few other hardware features, including a magnet and a sensor designed to power the board down when it is stacked upon another beacon.

Probing its various interfaces revealed nothing, as did connecting to the device via Bluetooth. However some further research as well as asking some McD’s employees revealed some of its secret. It does little more than advertise its MAC address, and an array of Bluetooth base stations in the restaurant use that to triangulate its approximate position.

If you’ve ever pondered how these beacons work while munching on your McFood, you might also like to read about McVulnerabilities elsewhere in the system.