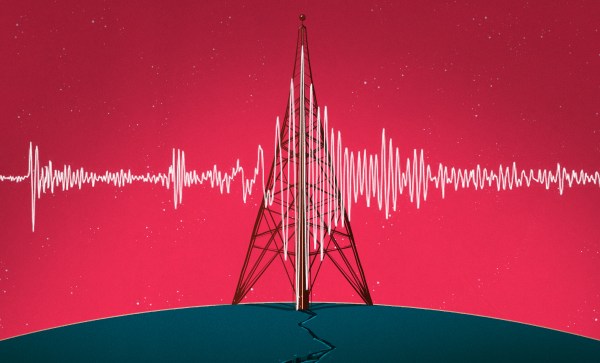

For all the successes of modern weather forecasting, where hurricanes, blizzards, and even notoriously unpredictable tornadoes are routinely detected before they strike, reliably predicting one aspect of nature’s fury has eluded us: earthquakes. The development of plate tectonic theory in the middle of the 20th century and the construction of a worldwide network of seismic sensors gave geologists the tools to understand how earthquakes happened, and even provided the tantalizing possibility of an accurate predictor of a coming quake. Such efforts had only limited success, though, and enough false alarms that most efforts to predict earthquakes were abandoned by the late 1990s or so.

It may turn out that scientists were looking in the wrong place for a reliable predictor of coming earthquakes. Some geologists and geophysicists have become convinced that instead of watching the twitches and spasms of the earth, the state of the skies above might be more fruitful. And they’re using the propagation of radio waves from both space and the ground to prove their point that the ionosphere does some interesting things before and after an earthquake strikes.