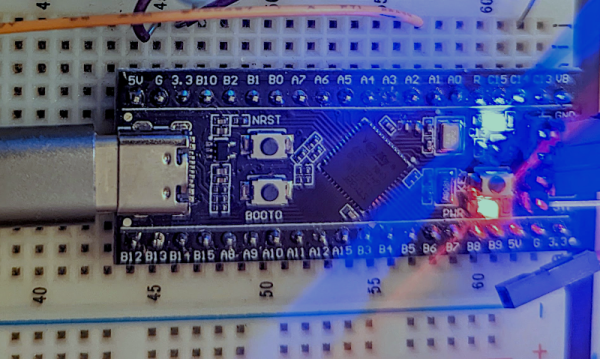

[Zak Kemble] likes to build things, and for several years has been pining over various Raspberry Pi products with an eye on putting them into service as a router. Sadly, none of them so far provided what he was looking for with regard to the raw throughput of the Gigabit Ethernet ports. His hopes were renewed when the Compute Module 4 came on scene, and [Zak] set out to turn the CM4 module into a full Gigabit Ethernet router. The project is documented on his excellent website, and sources are provided via a link to GitHub.

Of course the Compute Module 4 is just a module- it’s designed to be built into another product, and this is one of the many things differentiating it from a traditional Raspberry Pi. [Zak] designed a simple two layer PCB that breaks out the CM4’s main features. But a router with just one Ethernet port, even if it’s GbE, isn’t really a router. [Zak] added a Realtek RTL8111HS GbE controller to the PCIe bus, ensuring that he’d be able to get the full bandwidth of the device.

The list of fancy addons is fairly long, but it includes such neat hacks as the ability to power other network devices by passing through the 12 V power supply, having a poweroff button and a hard reset button, and even including an environmental sensor (although he doesn’t go into why… but why not, right?).

Testing the RouterPi uncovered some performance bottlenecks that were solved with some clever tweaks to the software that assigned different ports an tasks to different CPU cores. Overall, it’s a great looking device and has been successfully server [Zak] as a router, a DNS resolver, and more- what more can you ask for from an experimental project?

This CM4 based project is a wonderful contrast to Cisco’s first network product, which in itself was innovative at the the time, but definitely didn’t have Gigabit Ethernet. Thanks to [Adrian] for the tip!

Finding himself in such a boat, [Fletcher]’s solution was to build

Finding himself in such a boat, [Fletcher]’s solution was to build