With the incredibly low cost of software defined radio (SDR) hardware, and the often zero cost of related software, there’s never been a better time to get into the world of radio. If you’ve got $30 burning a hole in your pocket, you’re good to go. But as with any engrossing hobby that’s cheap to get into, you run the risk of going overboard eventually.

For example, if the radio gear inside your car approaches parity with the Kelly Blue Book value of said vehicle, you may have been bitten by the radio bug. In the video after the break, [Corrosive] gives us a tour of his antenna festooned Hyundai Accent, that features everything he needs to receive and analyze a multitude of analog and digital radio signals on the go.

For example, if the radio gear inside your car approaches parity with the Kelly Blue Book value of said vehicle, you may have been bitten by the radio bug. In the video after the break, [Corrosive] gives us a tour of his antenna festooned Hyundai Accent, that features everything he needs to receive and analyze a multitude of analog and digital radio signals on the go.

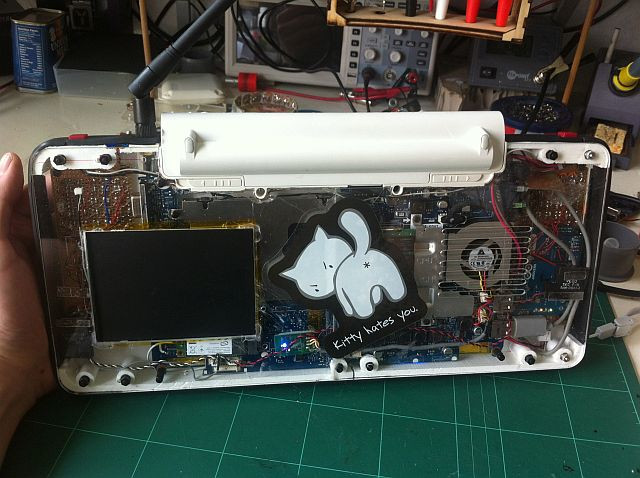

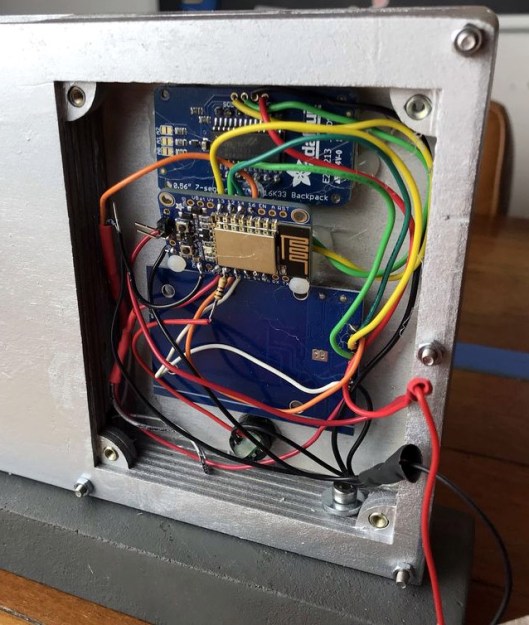

He starts with the roof of the car, which is home to five whip antennas (not counting the one from the factory installed AM/FM radio) and two GPS receivers. The ones on the rear of the car feed down into the trunk, where a bank of Nooelec NESDR RTL-SDR receivers will live in a USB hub. He’s only got one installed for test purposes, but he’ll need more for everything he’s got planned. Also riding in the back is a BCD780XLT scanner, which he got cheap on eBay thanks to the fact it had a dead display.

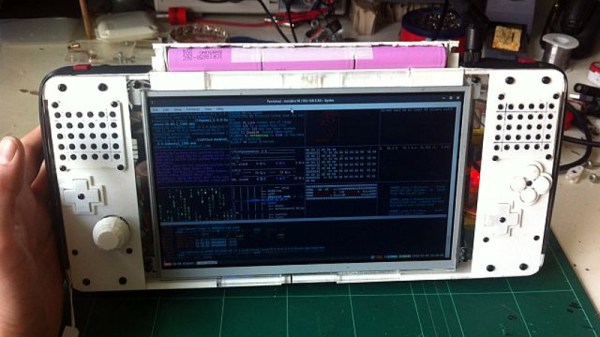

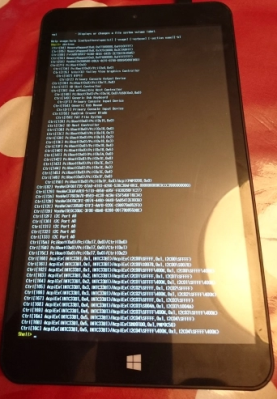

Luckily, where [Corrosive] is going, he won’t need displays. The SDR receivers and the scanner are all controlled from the driver’s seat by way of a Windows 10 tablet. This runs the ProScan software that provides a virtual interface to the BCD780XLT, as well as various SDR interfaces. He’s also got Gpredict for tracking satellites and ADS-B programs like Virtual Radar.

The car’s head unit has been replaced by a rooted Android entertainment system which supports USB host mode. [Corrosive] says it isn’t hooked up yet, but in the future the head unit is going to get its own SDR receiver so he can run programs like RF Analyzer right in the dashboard. We’re willing to bet that this will be the only car in the world that has both a waterfall display and the “Check Engine” light on at the same time.

Even if you aren’t ready to install it in your car, you might like to read up on using multiple SDR receivers for trunked radio or setting up your own ADS-B receiver to get a better idea of what [Corrosive] has in mind once everything is up and running.