Browsing YouTube may prove to be your largest destroyer of productive time outside of Hackaday, once you have started looking at assorted Lincolnshire plumbers or young Ukrainians doing dangerous stunts it’s easy to lose an hour with very little to show for it. There is so much to divert our attention, it’s a wonder that any of us ever make anything!

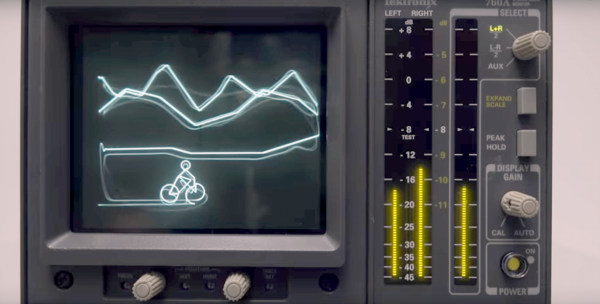

So to ensure you lose a further quarter hour today, we’d like to bring you [Jesper Broe]’s demonstration and teardown of his latest oscilloscope. This might seem unpromising when we tell you it’s a single-trace model with a bandwidth of 10MHz, but don’t give up. This is a RIMEDA C1-112, a portable instrument made in Lithuania when the country was part of the Soviet Union, and its party piece is that it contains a digital multimeter with a vector display using the oscilloscope CRT.

We’re shown the compact device being unpacked, then put through its paces as an oscilloscope. It gives useful results above 10MHz, but it is visibly losing amplitude and eventually it has trouble triggering as the frequency increases. Interestingly all the controls work in the opposite direction to the ones you will be used to, anticlockwise rotation increases rather than decreases. Then we’re shown the multimeter function, which is compared to a modern DMM and found to be still pretty accurate after nearly three decades.

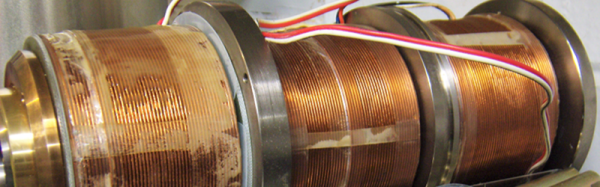

The ‘scope’s lid is then removed, and we see something of the logic boards that produce the digital display. A host of Soviet K155 series logic ICs are at the heart of it, and at the end of the video we’re shown a period review in Russian with a glimpse at the waveforms they produce to vector draw the figures.

Take a look at the video below the break, we’re sure you’ll agree it’s an instrument that many of us would still find useful today.

Continue reading “Soviet Portable Scopemeter Teardown” →