Sometimes it might seem as if your electronics are just jinxed. For [Niva_v_kopirce] it was the control board of his nephew’s RC car that kept frying the transistors. In situations like this, you can either throw it in the bin, invest your time in troubleshooting, hoping to find the error and try to fix it then, or get creative. He chose the latter, and designed and etched a replacement board.

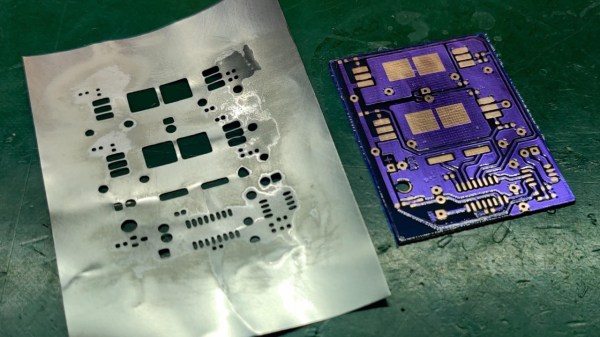

Of course, etching your own PCB isn’t that noteworthy for the average Hackaday reader, although [Niva_v_kopirce] did go the extra mile and added purple solder mask to it, turning the stylishness definitely up to 11. This is also where it gets interesting, when you think of the solder mask as complementary layer for a solder paste stencil. Growing tired of manually applying solder paste, he thought to give a DIY stencil a try this time — using a beer can.

After cutting the can open and flattening it, along with some sanding, he transferred the cutouts from the solder mask onto it, and started etching holes in it. While the result may not be exactly precise, it did the job, especially for a homemade built.

Despite their convenience, stencils are still a rather exotic addition for hobbyists as they rarely pay off for a one-off project with limited SMD component usage. But maybe this was a new inspiration for you now. And if etching metal is outside your comfort zone, cutting plastic can be an alternative, as well as 3d printing.